This book review was first published in the Fall 2004 issue of the International Tapestry Journal.

The Coptic Tapestry Albums & the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet

Nancy Hoskins, Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 2004

Nancy Arthur Hoskins’ recently published book, The Coptic Tapestry Albums and the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet, traces the history of a unique set of Coptic artifacts which now reside in the collection of the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle. Hoskins’ professional experience as a researcher, educator, writer and weaver provides the foundation for the book’s diverse topics, which include a discussion of the artifacts, the collector, the archaeological site and the creation and ownership of the albums.

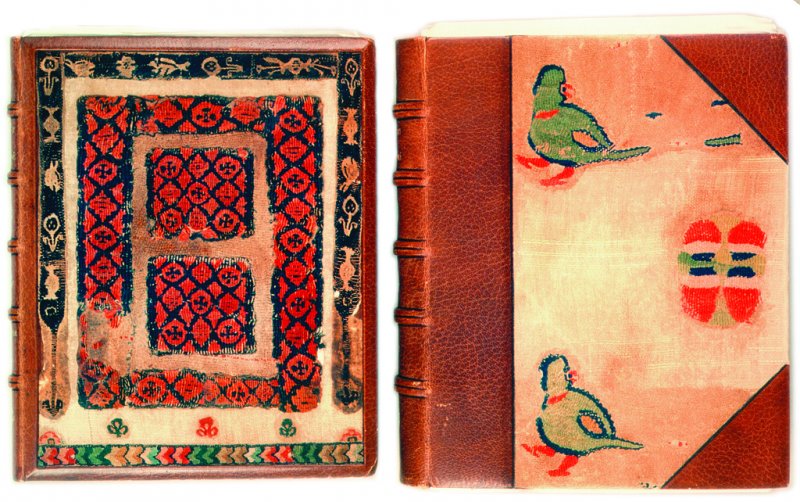

The Coptic Tapestry Albums include two bound books, the Text Album and the Textile Album. Albert Gayet, a French Egyptologist, collected the artifacts mounted within the albums. Hoskins lively account of Gayet’s career depicts an idiosyncratic man whose industriousness was matched by his pomposity. A traveling companion noted, “…on a steamy day Gayet dropped in for tea wearing a pair of pale lavender kid gloves.” 1 Gayet’s excavations took place primarily in Antinoé, a city founded by Hadrian in A.D. 130 which grew to become an important Roman trading center in Middle Egypt. By the 6th Century Antinoé’s significance had waned and in the early 19th century most of the city that was still above ground was dismantled and reused in construction projects elsewhere in Egypt. Gayet, whose archaeological campaigns were sponsored by Emile Etienne Guimet, the founder of the Musée Guimet in Paris, worked in Antinoé between 1896 and 1903. The artifacts excavated under his direction were exhibited at the Musée Guimet and at the 1900 World’s Fair held in Paris, where a young Henri Matisse was employed to paint the friezes of the Grand Palais. Hoskins discusses the influence that the Coptic tapestries might have had on Matisse, and other of the so-called Fauves, who were working in the early 1900s.

The Coptic Tapestry Albums contain mounted fragments of tapestries, plain weave plaids, embroideries and tablet weaves; a box enclosing fabric, a lock of hair, spindle whorls and a sandal; and two books authored by Gayet. The mounting of the artifacts and subsequent binding into the albums distinguishes this particular collection of objects. Henry Bryon, about whom little is known, probably commissioned the albums’ construction around 1913. The albums appeared in a Parisian auction in 1928 and then not again until Helen Stager Poulsen bought them in 1947 or 1948 from a Los Angeles bookstore. She, in turn donated the albums to the Henry Art Gallery in 1981.

Coptic tapestry occupies a venerable position among textile historians and practitioners. The finely woven, colorful images depict both pagan and Christian themes and exemplify the rich mixing that occurs when different cultures intermingle. Alexander the Great conquered Pharaonic Egypt in 332 B.C. The Romans subjugated Egypt in 30 B.C. and the Arab conquest occurred in 641 A.D. Each occupying culture left its mark on the art of Egypt. The Coptic Period is generally accepted to be the years between the late 3rd century A.D. and the Arab conquest. Hoskins carefully elucidates the range of textiles produced during this period, the materials and processes involved in their production and the structure of the textile industry, which was promoted and controlled by each successive foreign ruler of the Coptic people. Clear and detailed diagrams demonstrate the textile techniques used in the artifacts, including tapestry weave, tabby weave, tablet weaves, weft loop weave, sprang and embroidery. This section of the book will be particularly useful to both researchers and weavers.

Hoskins documents the Coptic Tapestry Albums beautifully with full color photographs that clearly show the structure of the cloth. The years of careful and thorough research that Hoskins has devoted to Gayet and the Coptic Albums reveals itself in the catalog entries, which describe the theme, style and structure of each textile and relate the fragments not only to textiles in the collections of museums around the world, but also to frescoes, sculptures, mosaics and manuscript paintings. She has been able, in some cases, to locate textiles in other collections that match the textiles in the Gayet albums. A closer look at a few of the textiles will reveal the diversity of the fabrics, the ingenuity of their makers and the unique nature of the albums.

Bound within the Textile Album, the Clavi and Cross Collage demonstrates the thoughtful approach of the person who created the albums. Eleven fragments from four different textiles are layered onto a blue plaid foundation fabric. The two vertical bands are examples of clavi, decorative elements on tunics. The principle garment worn during the Coptic Period, tunics are straight sided, loose fitting shirts consisting of a plain weave linen fabric that was sometimes ornamented with tapestry woven inserts. The inserts were an integral part of the fabric and were created by grouping warps in order to facilitate the production of a weft-faced fabric. The decorative tapestry elements take the shape of bands, squares, roundels and ovals. Clavus bands run from the back of the tunic, over the shoulder and down the front. Hoskins includes an illustrated description of how the weaving of tunics changed during different periods.

The vertical clavi in the Gayet collage contain a diamond motif that Hoskins associates with the patterns in Coptic window screens carved of wood. Her familiarity with Coptic textile collections led to the identification of matching tunic fragments in the Louvre museum. This association, in turn, connected two other fragments within the Gayet albums to the same tunic. Hoskins has reconstructed a possible arrangement for all of the matching fragments.

The roundels that terminate the clavus bands derive from a different textile. A gem-encrusted band encircles the central cross motif, which is, in turn, adorned with tiny flowers. Other fragments incorporated into the Cross and Clavi Collage include two bands containing nesting chevrons and a strip with alternating floral motifs. The fragments in this collage exhibit the use of decorative patterning and abstract imagery that characterizes certain Coptic tapestries. The Coptic practice of shifting the warp off the vertical axis and the weft off the horizontal axis, often referred to as eccentric weft, appears in the clavi bands where the triangles in the border move around the bottom curve. Also evident is the use of flying shuttle, or sketching weft, in which an independent yarn floats over rows of weft in order to create a thin line.

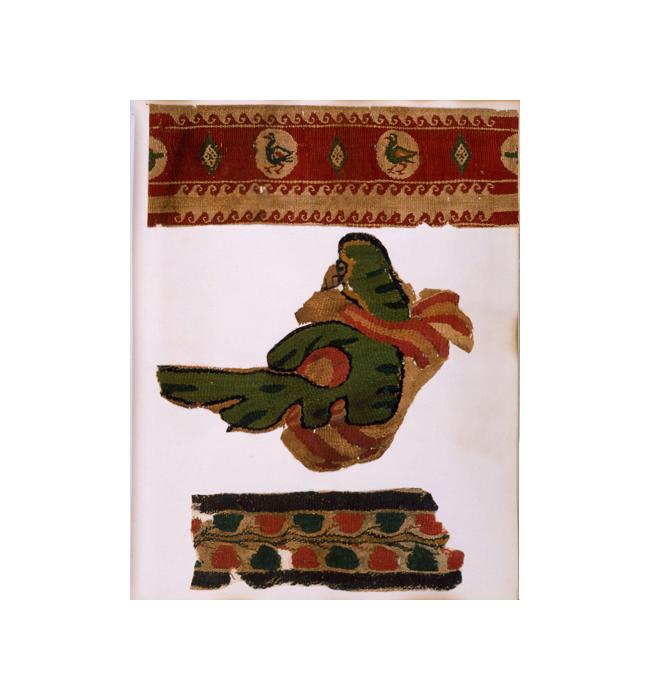

Eccentric weft is masterfully applied in the Bird with the Striped Scarf. The warp shifts and bends in different directions so that the weft flows like a river around the shapes in the bird. The still vivid colors, the simple, yet suggestive rendering of the bird and the unexpected scarf add to the charm of this avian creature. A small piece of the tabby linen weave from which this fragment was cut is visible below the scarf. Many of the Coptic textiles in museums were collected at a time when archaeological practices were still in a formative stage. Textiles were often cut into small pieces and sold separately with little concern for the loss of contextual integrity. Gayet, himself, left little documentation with his collections. Although he trained as an archaeologist, his methods were not always the most scientific. His belief in the occult, and his consultations with a certain Monsieur X, influenced his interpretation of certain artifacts. It is only through the sleuthing of researchers such as Hoskins that a partial history of these textiles can be reconstructed.

The Interlace Patterned Clavus and Square is an example of a large genre of monochrome tapestry woven designs in which most of the image is defined by the aforementioned flying shuttle, or sketching weft. In this case the sketching weft is linen. The fine lines produced by this technique are particularly well suited for intricate, linear patterns. The square contains an inner design of the endless knot pattern, surrounded by a twisted rope and an entwined cable design. At the bottom of the clavus a skein design surmounts a framed cross. The clavus and square were originally part of a tunic.

Interlace patterns are common in many cultures and Hoskins discusses some of the meanings that have been attributed to them, among them protection from the evil eye. “Fine linen lines forming patterns that endlessly knot, plait, entwine, and interlace were thought to transfix the viewer’s gaze, thus protecting the person wearing it from the evil eye.” 2

Wool; Linen, 10 1/2 x 7 7/8 in. (26.7 x 20 cm) overall; 11 1/4 x 9 3/4 x 2 3/4 in. (28.6 x 24.8 x 7 cm) closed size overall; 11 1/4 x 18 5/8 in. (28.6 x 47.3 cm) open size, Helen Stager Poulsen Collection, TC 83.7-72, t1, Henry Art Gallery

Perhaps the most unusual collage in the Coptic Tapestry Albums is the Boxed Collage, a collection of textiles, textile tools, leather, the sole of a sandal and a lock of hair. The assemblage is a miniaturized version of the sixteenth century cabinet of curiosity, in which diverse objects from foreign lands mingle. Carefully composed and constructed, the collage pays silent tribute to a man whose methods may not have been the most exacting but whose life and work have added to the legacy of Coptic textiles.

The Coptic Tapestry Albums and the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet, adds a fascinating chapter to Coptic scholarship. The very readable and informative text, supplemented with a wealth of illustrations, diagrams, appendices and a lengthy bibliography will not only enlighten the reader about a very unique collection of Coptic artifacts, but also offer avenues for further reading and practical application.

End Notes

- Hoskins, Nancy. The Coptic Tapestry Albums & the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet. Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 2004 Eugene, Oregon: Skein Publications. 6

- Hoskins, Nancy. The Coptic Tapestry Albums & the Archaeologist of Antinoé, Albert Gayet. Seattle: The University of Washington Press, 2004 Eugene, Oregon: Skein Publications. 101-102