This article was first published in the American Tapestry Alliance’s newsletter, Tapestry Topics, Spring 2006.

The Queen’s Tapestry

Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle, WA, 2005

In 1904 Professor Gabriel Gustafson began excavations on a burial mound located in Oseberg, Norway. The site, which dates to the ninth century, is the only known Viking grave containing exclusively the remains of women. Two female bodies, one a generation older than the other, were interred within a burial ship and accompanied by household goods, textiles and weaving tools. The Oseberg remains came to the attention of Sol B. Baekholt during her graduate studies. Baekholt was the first woman in Norway to graduate with a master’s degree in pictorial weaving from the Norwegian College for Teachers of Arts and Crafts. Since her graduation, she has committed a significant portion of her career to publicizing the beauty and variety of the artifacts in the Oseberg burial ship.

In 2004 Baekholt designed a series of narrative tapestries, several silk rugs and sets of both porcelain and silver to commemorate the centenary of the Oseberg excavation. Artifacts from the actual site inspired the designs for these objects. The collection has toured internationally, and it hung, during the fall of 2005, at the Nordic Heritage Museum in Seattle, Washington.

The centerpiece of Baekholt’s independently financed exhibition is The Queen’s Tapestry, a 3 foot by 78 foot tapestry that depicts the artist’s interpretation of the life of the woman laid to rest within the Oseberg burial ship. Baekholt chose the narrow, horizontal format, reminiscent of the Bayeux Tapestry, because ancient Norwegian poetry contains references to pictorial runners, or revler. 1 The linear, chronological narrative contains eleven scenes, beginning with Alhvid’s childhood and ending with the transport of the burial ship to the Viking Ship Museum in Bygdøy, Norway, where it is located today.

The images in the tapestry include depictions of actual objects found on the burial ship, as well as imagery from the pictorial weavings included among the burial goods. The burial ship itself figures in many of the scenes. The patterned borders that enclose the narrative also derive from motifs found on Oseberg artifacts. The source material used in the tapestry is augmented and enriched by the imagination of Sol Baekholt.

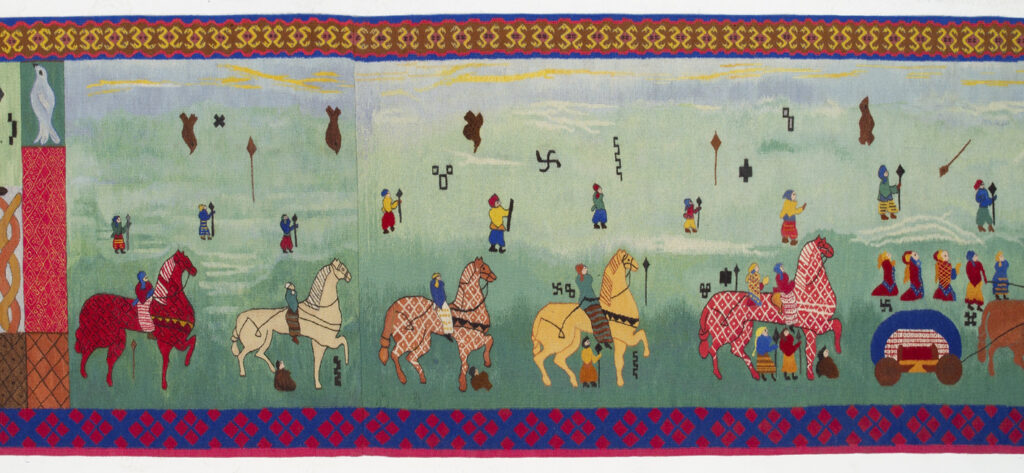

Midway through the narrative, Alhvid marries King Gudrød Gjaeve. Colorful, prancing horses pulling carts lead the procession across a landscape of subtly shifting colors. Riders mounted atop patterned steeds follow. The horses’ tails are braided and then knotted in the middle with the bottom hanging free. Braids were thought to ward off sorcery while knots were believed to secure eternal, lasting love. Designs such as the swastika, symbolizing good luck, good fortune and peace and the spear, symbolizing the life force, float through the field of the tapestry. 2

In a portrayal of daily life, Baekholt illustrates the processing of wool, spinning and weaving. The burial ship contained many weaving tools, including wool shears, dye kettles, drop spindles, circular and ribbon looms, and tablets for card weaving. In the tapestry, kettles of water boil for washing and dying wool and a woman spins, while two other women weave on vertical tapestry looms. Baekholt mentions that, in addition to linen and wool, goat hair and nettles were also used in the ancient Oseberg textiles. 3 In the background, cloth hangs on a line to dry. Two tents, modeled on the actual tents found on the burial ship, are pitched under the trees.

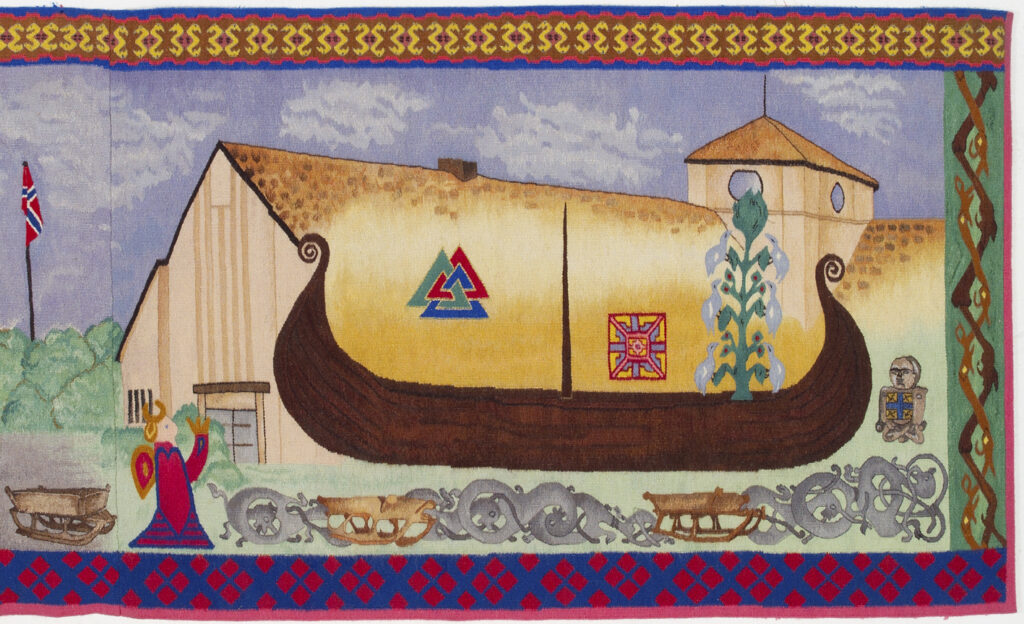

The final scene shows the Oseberg ship in front of the Norwegian Viking Ship Museum. The ancient burial ship was pulled along portable railroad tracks to the sea and then transported by barge to Bygdøy. This scene in the tapestry also shows the richly carved, ceremonial sledges found in the gravesite.

Baekholt employed five Polish tapestry artists to complete The Queen’s Tapestry. The tapestry combines hand dyed Norwegian spelsau woolen weft with a linen warp. The Vikings favored the resilient spelsau sheep and brought them along as they settled in foreign lands. The tapestry was woven in sections that were assembled after the weaving was completed. With this knowledge it is possible to identify the different styles of the participating weavers. Because of the enormous length of the tapestry and the folkloric style of the imagery, the technical variety does not detract from the charm of the piece. Baekholt is to be congratulated on the completion of such an ambitious project.

End Notes

1 Sol Baekholt. “Scenes from The Queen’s Tapestry,” unpublished.

2 Sol Baekholt. “Scenes from The Queen’s Tapestry,” unpublished.

3 Sol Baekholt. “Scenes from The Queen’s Tapestry,” unpublished.