This article was first published in the American Tapestry Alliance’s newsletter, Tapestry Topics, Vol. 32 No.2, Summer 2006.

“… If the artist is not traveling into the unknown, what is the point of the effort (Higby 3)?”

Creativity is not only one of the most sought after human attributes, it is also one of the most elusive. Personal accounts of creative moments often focus on a sudden insight, an “Ah, Ha!” experience. Researchers, however, describe the creative process as a series of steps, of which the aforementioned “Eureka” is but one. A common model involves the following stages: First Insight, Saturation, Incubation, Illumination and Verification (Edwards 4). How these stages manifest themselves can be highly variable and unpredictable and is one of the reasons the creative process is considered so mysterious. For many artists the creative process involves a certain amount of risk, such as the risk of exploring the unknown in order to discover new directions. In this article I will draw on the experiences of two artists, Linda Wallace and Sharon Marcus, to illustrate the variability and complexity of the creative process and the role of risk within that process.

An artist’s First Insight involves the discovery of questions, or challenges, that become the focus for the work. Albert Einstein said, “The formulation of a problem is often more essential than its solution, which may be merely a matter of … experiential skill. To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old questions from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advances…(Einstein)”

How do artists stimulate this stage of First Insight? For Sharon Marcus, interrogative writing serves as a fruitful method for generating new ideas. Through written reflections on completed work and ideas that the work has generated, she discovers new lines of investigation. As written language, these new ideas exist as abstractions, concepts that have not yet found physical form. During this early phase of inquiry Marcus may explore the ideas through computer imagery or through experiments on the loom.

Although risk taking may be present in any stage of the creative process, First Insight often involves the most personal risk because it requires letting go of what is comfortable and known in order to discover new paths. This process is often highly intuitive and has no guaranteed outcome. Probing the universe of the unfamiliar is, for Marcus, essential to her growth as an artist. “I really try to follow my instincts about what ‘feels’ right (Marcus).” Projects that do not pose new challenges do not retain her interest.

For Linda Wallace, finding new directions for her work involves both observation and daydreaming. By exposing herself to stimuli such as books, magazines or experiences in nature, and by keeping an open mind, ideas rise to consciousness. Wallace speaks of this part of the creative process as a “disengagement of my linear mind. Space is a good word for the drifting phenomenon, thoughts floating, touching down, finding connections both profound and banal. No design pressure. No judgment (Wallace).”

Although Wallace does not characterize herself as a risk taker, she does acknowledge the importance of open-ended exploration. “If you knew where the road was leading, why go down it? It’s the mystery of what might be around the next bend – in art and in life – that … draws me in (Wallace).”

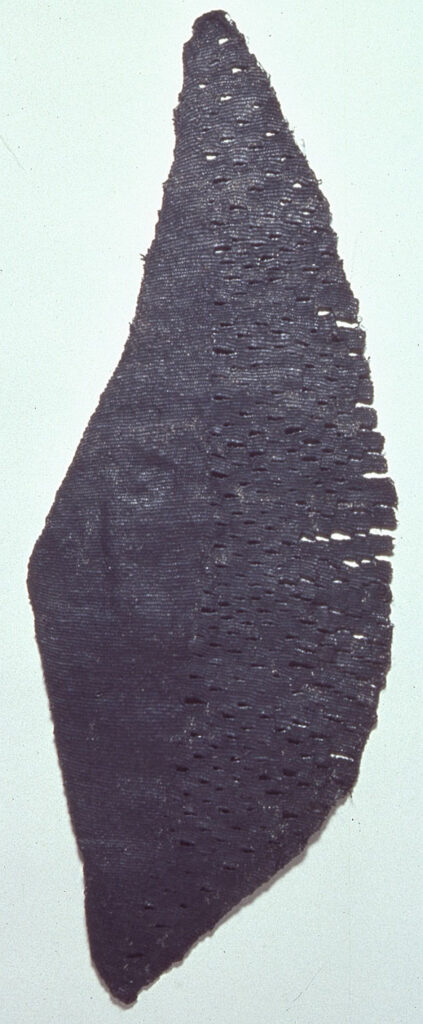

The second stage of the creative process is called Saturation. It involves researching the area of interest that was discovered in the stage of First Insight. Sharon Marcus’ work often involves research. In the multi media series Notes From Lake Mungo, Marcus brought to visual form her experiences at a remote site in Australia. Her first visit to the area preceded any research about its history or geography. Her objective was to engage directly with the site, allowing it to guide her thoughts and artistic interventions. Later she read about the early history of Australia, imagining how that history might have affected the residents of the now deserted Lake Mungo. The series of artworks that arose from Marcus’ experience at Lake Mungo reflect the intersection of physical site and history. In Site she incorporated materials that were, or would have been present, at Lake Mungo and employed weaving and finishing techniques that evoked the landscape.

For Wallace, careful thought and thorough research are critical to her process. Part of Wallace’s research involves determining how to represent complex social issues in visual form. Preliminary drawings explore the ways in which images might symbolize the issue. She also addresses other questions at this point, such as, “What medium? What imagery? What size? More importantly, what do I want to say and who is my audience (Wallace)?” The understanding gained from research creates depth and complexity in her artistic projects.

Wallace’s series on infertility started with an interest in women in European history who were unable to produce an heir. For the Tears of Queen Anne relates the story of the English queen, who, pregnant 18 times, gave birth to only five living children. None of the boys survived to inherit the throne. This series developed into an exploration of bioethical issues. Conundrum and One reflect Wallace’s research into women’s responses to current fertility technologies.

Sometimes Wallace’s research process stalls. “… the project is gently put back on its shelf, the ideas further developed, filed away to be brought out and examined again (Wallace).” Wallace refers to the various stages of the creative process as interconnected. Questions beget research. Research begets more questions. The non-linear nature of Wallace’s experience is typical for many artists. Marcus experiences similar phenomena in her writing. In pursuit of one idea many more questions arise.

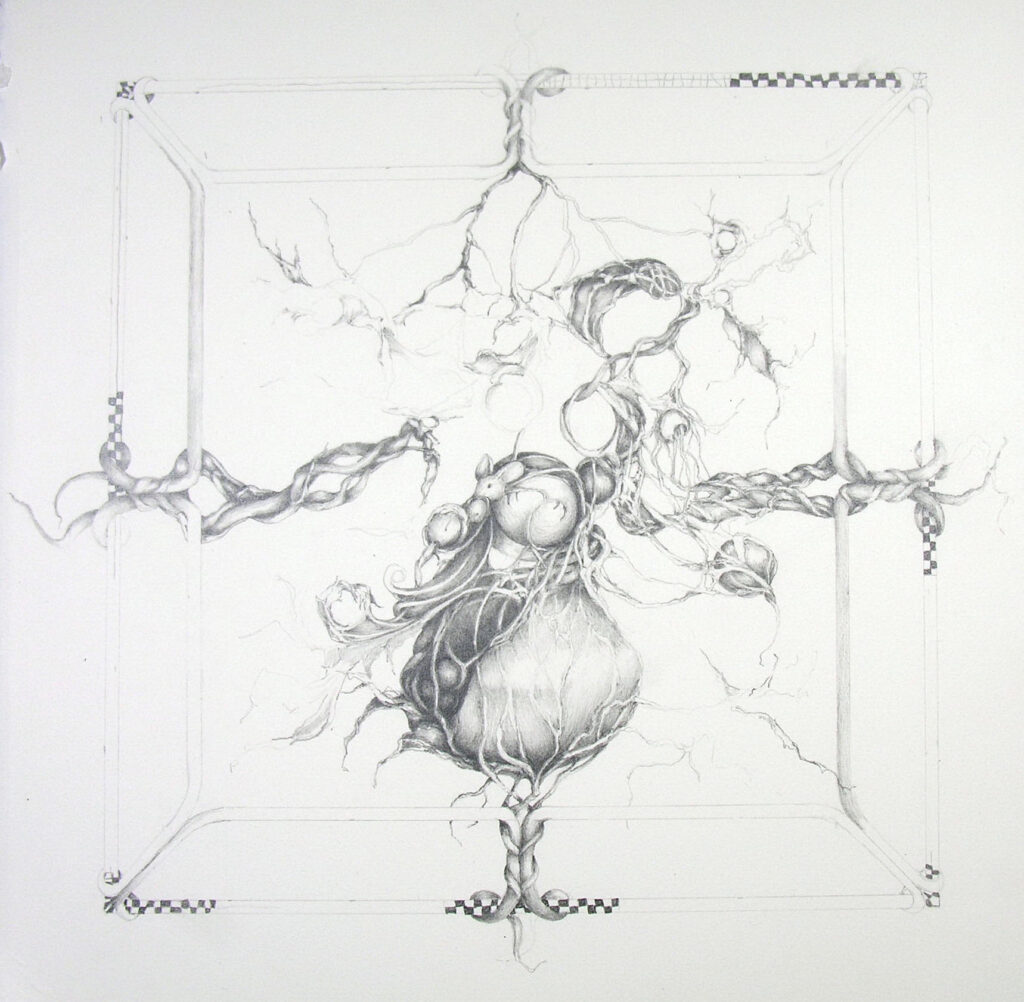

The third stage of the creative process is referred to as Incubation. This might involve stepping away from the problem, or talking with others. Wallace engages in correspondence with others, exchanging thoughts and ideas. She rarely, however, discusses actual pieces. For those decisions she trusts that the time and effort put into her work will lead to a solution. Drawing is also important at this stage. Drawings such as the sketch for Homage to Aubrey render in visual form the initial question and subsequent research. Many of Wallace’s drawings do not become tapestries. They are simply another way of contemplating the question.

For Marcus the Incubation stage often involves self-reflection, scrutinizing her process in order to resolve doubts. Marcus’ propensity for writing manifests itself in this stage as she records her thoughts about her work, keeping a record that will become a valuable reference.

Illumination, or the “Eureka!” phase, is defined as the discovery of a solution, or an approach, to the question. This might involve a realization of what methods could be used to represent the issue in the artwork. In some cases the illumination reveals a truth. In other cases one realizes that the question is more important than the answer, or that the question is unanswerable, or the answer ambiguous. Although some of Wallace’s images have come to her quickly, others are worked and reworked over a longer period of time that involves additional research and rumination. For her, the process of searching for truth is more important than finding a final solution. Her goal is to illuminate the complexity of the issues and to stimulate the viewer to engage with the questions.

In speaking of this complexity, Linda Wallace says, “No matter what stage my work has reached, I’m always operating at all the levels… I take frequent breaks from weaving. I correspond, I read, I think, I draw, I sit and let my mind drift as my eyes flick from piles of richly colored yarn, to sketches, postcards, and objects pinned to the studio wall (Wallace). “

For Marcus, characterizing this stage as a flash of insight does not acknowledge the work that takes place during the Saturation and Incubation stages. She prefers to contextualize these insights within the framework of the reading, writing and thinking that occurs throughout her creative process. Marcus considers most of her work to be the quest for a truth that underlies a particular line of investigation. For her, this truth encompasses a multidimensional set of qualities, which may themselves involve ambiguity or multiplicity in meaning.

In the theoretical model of the creative process the last stage is referred to as Verification, the testing of the solution that arose in the Illumination phase. For an artist, this usually involves making an art object. For most artists the actual making of an object also involves a degree of risk because working with specific materials and techniques is malleable and open to experimentation. For tapestry weavers, taking risks in the making can be especially difficult because the process itself is so laborious.

Wallace weaves her tapestries from fairly complete drawings. For her, more risk occurs during the conceptualization and drawing stages than during the weaving. Her drawings, however, are black and white. She chooses colors during the weaving, a method which entails a certain amount of risk. Wallace considers the first color choice to be critical, as it governs many of the decisions that follow. Wallace chooses colors for their symbolic significance, their relationship to the image and their relationships to each other.

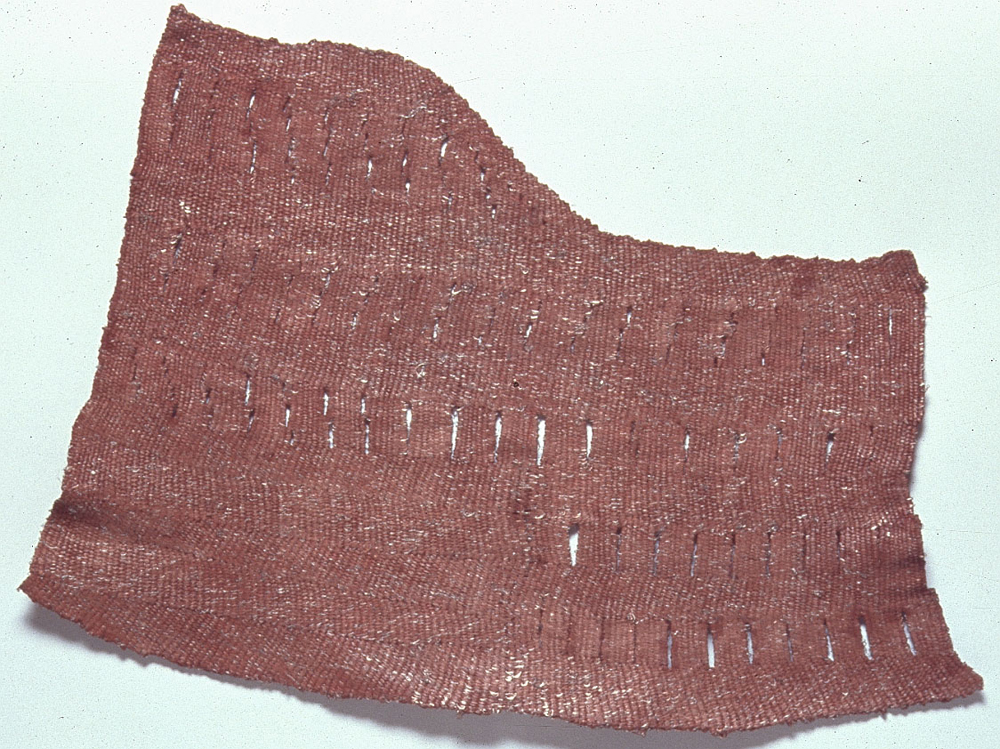

Sharon Marcus characterizes her most recent series, Personal Knowledge, which includes the tapestry Facade, as “absolutely the most risky studio undertaking in my work so far (Marcus).” In this series the post weaving washing, pounding and burnishing of the fabric surface add further aesthetic and conceptual complexity to the work. This technical experimentation has, in turn, stimulated new questions and directions.

For Linda Wallace evaluating the success of her work involves determining whether it embodies the concepts and issues about which she has been thinking. She considers the project from multiple perspectives and usually finds that this stage leads to new lines of investigation, another opportunity to take the risk of trusting her instincts and opening herself to the creative process.

Marcus’ evaluation of her work, like the rest of her creative process, is purposeful. Her goal is to stay “truthful to my instincts (Marcus).” She feels this evaluation is even more critical because of the time consuming nature of tapestry weaving. If a piece feels wrong, she has no qualms about starting over, or abandoning it. Her goal is to create meaning in her work through the interaction of content and process.

One must be careful to avoid dogmatic thinking when describing creativity as a process of steps. As the two artists quoted in this article demonstrate, the creative process is highly variable and individual. However, it is not necessarily mystical or controlled by chance. The techniques that Marcus and Wallace employ as stimuli to formulating new directions are examples of how artists encourage original thinking and the development of new paths in their work. The investigation of those paths during the research and contemplation phases adds richness and the final verification stage allows for self-assessment. The creative process involves both the more unpredictable elements of exploration and insight, and the more analytical elements of research and evaluation. It is an interchange between serendipity and intention, a balance between imagination and analysis. Work that springs from an open-minded curiosity and, through the intellectual, emotional and technical investigation of the artist, unveils surprising associations, reveals a creative mind at work.

References

Edwards, Betty. Drawing on the Artist Within. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986.

Einstein, Albert and Leopold Infeld. The Evolution of Physics: From Early Concepts to Relativity and Quanta. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1966.

Higby, Wayne. “Expectation: Art, Materials and the Photograph.” Haystack Monograph Craft in the 90s: A Return to Materials. Deer Isle, Maine: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1991.

Marcus, Sharon. Personal Interview. March 2, 2006.

Wallace, Linda. Personal Interview. March 2, 2006.