This article was first published on the blog, Selfies in Tapestry, and then in the American Tapestry Alliance newsletter, Tapestry Topics, Vol. 42, No. 1, Spring 2016

Thank you Australia…

The word “selfie” first appeared in a 2002 post by Australian Nathan Hope on Karl Kruszelnicki’s Internet forum, Dr. Karl Self-Serve Science Forum. Nathan had written to ask about self-dissolving stitches in his lower lip that patched up an injury from a late night brawl. He posted a picture of his face and added, “And sorry about the focus, it was a selfie,” conveniently shortening a word and adding a vowel, as Australians are want to do.

In its more restricted usage, “selfie” refers to a self-portrait taken with a hand held camera, or camera phone. Strictly speaking, then, most of the images on the Selfies in Tapestry: Slo Art in the Age of Quick blog are not selfies, although some of them may be based on selfies. As a subset of self-portraits, selfies are distinguished by being disseminated, most commonly, on the Internet. Here again, the Aussies were the first.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall…

Most self-portraiture involves a device that allows the artist to look at herself. Although looking at a reflection in a pool of water might have been the first self imaging aid, the history of self-portraits follows closely the development of the mirror. Mirrors of polished stone date back about 6000 years; metal mirrors are documented from Antiquity. The first mention of a mirror used as an aid in the production of a self-portrait is in the 1st C B.C. when Pliny refers to Iaia of Cyzias. The mirror Iaia used would have been polished metal. (Hall, 21) In Medieval Europe, small convex glass mirrors were expensive and highly prized, not just because of their ability to produce a clear, if distorted, reflection, but also because they were considered to be truth tellers, symbolic of knowledge and introspection. In the latter sense, they are connected with the goal of personal salvation, and so, by association, a self-portrait is often seen as a search for the individual soul. The combination of these technological and socio/psychological factors fueled the development of a tradition of self portraiture in Medieval Europe.

“The eyes are the mirror of the soul and reflect everything that seems to be hidden; and like a mirror, they also reflect the person looking into them.” Paulo Coehlo

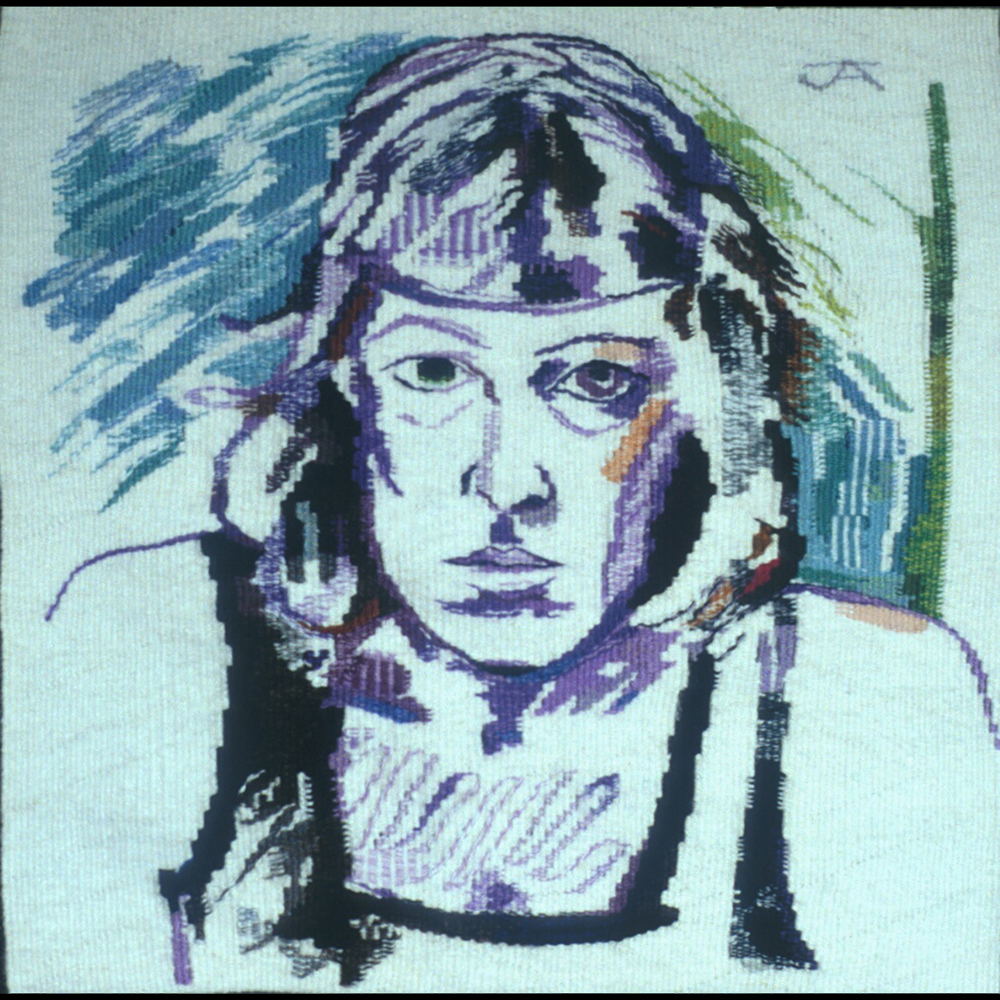

Self-portraits are often noteworthy for the intensity of the gaze. In Janet Austin’s “Self-portrait in Color” and “Self-portrait (Purple Sketch)” the probing nature of her expression reflects the many hours that the artist has looked at herself as she painted the self-portrait that served as the maquette for her tapestry. The eyes are searching, the mouth fixed, the countenance intent. The two self-portraits express the concentration involved in looking, seeing, understanding and representing the self. After spending so much time looking at oneself anyone might begin to wonder about the nature of the self, about what it is that is truly you, and how it can best be represented.

Many cultures see the eyes as a mirror of, or path to, the soul. As the dominant sense, vision, and its instrument, the eyes, are the way we know the world. And, so, by extension, looking at our reflection is an important component in our understanding of our self. A self-portrait, and the investigation that it entails, allows the artist to address herself directly, to use art making as a way to probe the nature of the self. In the making, a self-portrait is a monologue, a self-confession. When shared with others, it becomes a statement about oneself.

“Self-portraiture is a singular in-turned art. Something eerie lurks in its fingering of the edge between seer and seen.” Julian Bell

Although self-portraits look inward, they also look outward to the viewer. We feel the artist is looking at us, but we also know that the artist was looking at herself. We are put in the place of the artist. We stand where she stood. In self-portraits the artist has become the art. Is the person in the self-portrait the subject or the object? Is the image first person or third person?

Fast forward to the past

By the 12th century, an increasing focus on both the individual, and on an artisan’s skills, results in the appearance of self-portraits showing the artist at work, or perhaps showing the artist presenting the actual illuminated manuscript that includes the self-portrait, to the patron who commissioned the work. Self-portraits showing the artist at work offer visual proof of the artist’s industriousness and skill and could have served as a form of self promotion, a business card of sorts.

In Sarah C. Swett’s contributions to Selfies on Slo, she pictures herself: contemplating herself at work – “Who Is in Charge”; wishing she could be at work – “Please, Can you Pass me my Knitting?”; and wondering what being an artist is all about – “I Dunno.” “Who’s in Charge” pictures the artist, whose face is mostly unwoven and undefined, other than one pensive eye. She is taking a moment to turn away from her loom and reflect. Her self-representation in the tapestry, meanwhile, is in suspended animation, while she waits for the artist to decide what the two self portraits in the tapestry are going to be weaving. Perhaps it is this state of suspended animation in which artists might find themselves, that leads Swett to picture herself hung to dry on the laundry line in “Please, Can you Pass me my Knitting.” The artist dangles hopelessly out of control in a work of her own making. The artistic climate in the 20th and 21st centuries is marked by a dizzying plethora of ways of thinking about and executing art. It could lead any artist, as Sarah does in “I Dunno,” to scratch her head. But, the open-ended options are thrilling and nowhere more so than in self-portraiture. For what self-portrait is truly literal?

“And after all, what is a lie? Tis but the truth in a masquerade.” Alexander Pope

“Every painter paints himself” Girolamo Savonarola

In “Send My Roots Rain,” “Blond Boy with Bike” and “Vietnam War Conscientious Objector” Anton Veenstra masks his visage by fashioning it out of buttons. The fragmented image that results from the materials suggests the multifaceted and sometimes contradictory nature of our personalities. Can the shifting group of experiences that make up our lives ever be summed up in one easily understood, contained and well-defined image of the self?

In other tapestries Veenstra pictures himself as Apollo, Billy Idol and others. He remarks, “…you weave slowly, and elements of the self-portrait cannot fail to intrude.” And, in the sense that art is an expression of the artist’s thinking and being, what act of making is not a self-portrait? Masquerade and role-playing might suggest that life is similar to theatre, a stage upon which we perform our self, trying on different characters, constantly remaking our self as we (self) construct our identity. Or it might suggest, that underneath all the superficial features that define us, we are really all the same.

And then …

Is an image of one’s face the only, or even the best, way to portray the essence of your self? In “Hands On/ Slow Selfie” Janette Meetze depicts herself through her hands. Nine different hands in a variety of positions remind us of what an anatomical and functional marvel the hand is. As an artist, perhaps she thinks that her hands represent most fully her self. In reference to a faceless self-portrait in “Rainfall,” Ruth Manning asks, “Can a face with no features be a selfie?” What part of the mind/body complex truly distinguishes us as ourselves?

Fast forward to the past

By the 14th and 15th centuries superior mirrors became available and cheaper, and self-portraits became even more common. Artists appear in their own paintings of mythological, historical and religious stories. Many artists paint themselves over their life time, leaving a legacy of self-portraits that serve as an autobiography. Perhaps this kind of chronological record, such as that seen in the work of Anton Veenstra, represents more accurately the multifaceted and shifting nature of who we are throughout our lifetime.

While time and different aspects of one’s personality might be presented over a series of images, Margaret Sunday, in “penelope dissembling in frackutopia” weaves a series of strips and assembles them in order to create her self-portrait. The strips build up in a geologic, sedimentary fashion: references to local fracking; a compromised skeleton; a drawing of a cast of her face from an earlier age. The montage of past and present, of environmental and physical factors creates a multidimensional representation of the influences that determine who she is. Her hand, the instrument of her labor, breaks free from the top edge in a gesture that suggests she is waiting to receive something. Wisdom from Penelope’s perseverance in the face of adversity? Self-knowledge? Perhaps it is the human induced seismic activity that has produced this fractured fairy tale.

Have we arrived yet?

The development of photography made self-portraiture much easier. However, does the supposed veracity of photography offer us any help in truly representing the self? Are we really as neat and tidy and as two dimensional as a photo suggests? Or do self representations that involve time in their execution, a variety of media, and references to social, historical, cultural and psychological dimensions reflect more clearly the messy nature of our beings? And, in either case, are we destined to play a game of hide and seek, cat and mouse, as we doggedly pursue the elusive and veiled self?

References

Julian Bell, 500 Self-Portraits. 2004, Phaidon.

Paulo Coehlo, Manuscript Found in Accra. 2012.

Laura Cummings. A Face to the World: On Self-Portraits. 2010, Harper Press.

James Hall. The Self Portrait: A Cultural History. 2014, Thames & Hudson.

Alexander Pope

Girolamo Savonarola, Sermons on Ezekiel. Lent, 1497.