This paper was first presented at the Textile Society of America’s 2004 Symposium and was subsequently published in the Symposium Proceedings.

“The artist anywhere lives at the edge of the sea: All that possibility of form, of material, of meaning. The sea is deep and bountiful. And you are deep. You pick up a few fragments that have been tossed up by the waves, and turn them over in your hands.” 1

Sharon Marcus’ career as an artist, educator, writer and committed advocate for contemporary tapestry spans nearly three decades. Marcus’ intellectual curiosity and creativity contribute to her international reputation and position her work within a broader artistic dialog whose intent is not only aesthetic, but also conceptual. Trained in anthropology and archaeology, Marcus excavates the elusive and evocative facets of human habitation and landscape in her woven tapestries. She has also explored the political and social implications of such scientific and artistic interventions. My task, as interpreter, will be to follow the artist’s path of inquiry, pointing out how her methods reinforce the content of her work and positioning her creative investigations within contemporary art theory and textile practice.

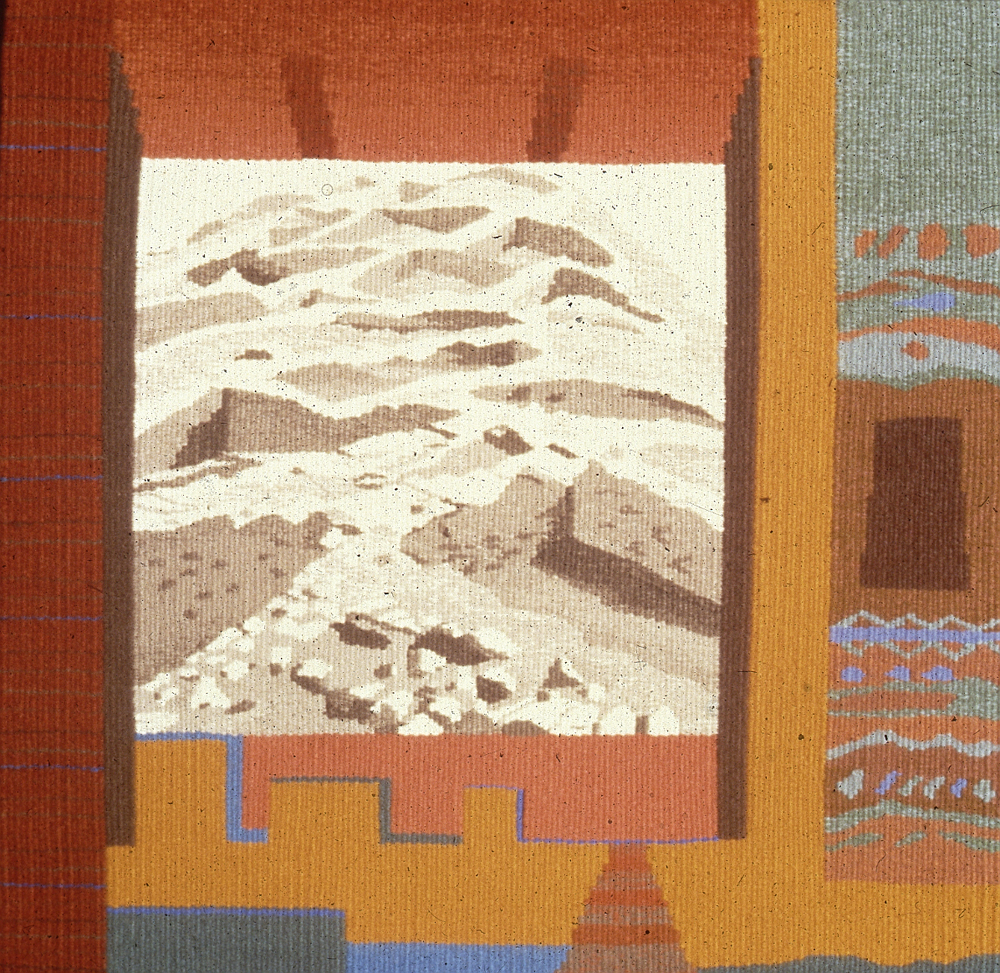

Throughout her career Marcus has manipulated images of architecture and landscape in order to investigate formal and conceptual concerns. Through collage and computer manipulation she deliberately transforms an image, carefully reconstructing the composition to develop the intellectual content of the work. In early pieces, such as Anasazi Ruins, from 1984, suggestions of architectural details create a dynamic framework surrounding barren, rocky ground. The darkened opening on the right, a motif encountered often in Marcus’ work, suggests the difficulty of knowing the past. For archaeologists and anthropologists, reconstructing the past involves discovering and ordering evidence that is often fragmentary. Collage also involves working with fragments. In Anasazi Ruins the elements combined within the design represent different times and different perspectives. Flat patterned surfaces confront three-dimensional forms. Disparate combinations such as this offer an alternative representational mode. In the Western tradition linear perspective fixes the viewer’s position outside the picture frame. In Anasazi Ruins and Maghreb different places, perspectives and moments in time cohabit, creating an image in which the viewer’s position moves. This approach more closely reflects the way we come to know the world, through a synthesis of experiences and vantage points. 2 In these pieces Marcus replaces archaeology’s emphasis on objectivity and the creation of a seamless, linear narrative for a more subjective, experientially based view of landscape and human history. The collaged image also points out the very deliberate and mediated nature of representation, implying, in turn that our knowledge of the world is constructed, and not given.

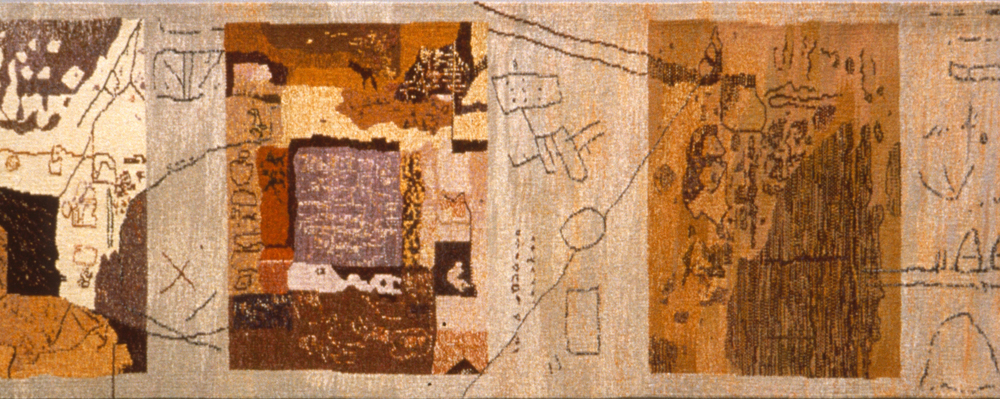

Marcus continues her investigation into how we know, and represent a place in The Enigma of Les Baux, woven in 1990. The ruins of Les Baux – the former chateau, the village homes and the bauxite mines became the subject of several tapestries in which Marcus collaged photographs, drawn images and found marks. As with all of her tapestries, the cartoon was developed in black and white and colors were selected by winding fibers directly onto bobbins, keeping in mind the value relationships within the original images but disregarding the hues.

Images such as The Enigma of Les Baux and the later tapestry, Treasure the Dream, challenge traditional notions of sequential narrative development. The layering of images, the deliberate confusion of space and the noise introduced by the appropriated, graffiti – like text emphasize the inherent ambiguity and complexity involved in any representation of the past. These images might be more appropriately considered to be allegories. In Craig Owens’ seminal essay, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” the author speaks of the doubling, or retelling involved in allegory as one way in which the past is reclaimed and brought forward into the present. 3 At the same time, the retelling, because it can never be identical, necessarily becomes commentary, or exegesis. Marcus’ complex and densely layered images re- present ancient ruins and formerly inhabited sites. But these representations do not strive for impartiality. They are not transparent windows on the world, proclaiming a unified and absolute meaning. Instead, the viewer is invited to excavate the image in order to ascertain the artist’s intent. The patchwork of perspectives asserts a more contingent and shifting landscape in which different, often-contradictory views have equal validity. They suggest the complex interweaving of nature, culture and ideology that influence the history of a place.

One of the hallmarks of the so called postmodern, is the borrowing, or reuse of images, specifically for the purpose of commentary. In this sense, Marcus’ use of borrowed text in Treasure the Dream, sits squarely within contemporary art practice. Appropriated images carry with them their own meaning but in their new context, they also absorb supplemental meaning. It is the interaction between these meanings that offers such great potential for commentary.

In Marcus’ case the exegetic function of the image focuses on how we know the past. In Departure she rejects the traditional approach of claiming knowledge through a systematic ordering of fragmentary evidence for a more open- ended dialogue, which emphasizes the complex and often messy nature of historical evidence. This attitude is reflected in the artist’s use of earthy, scumbled colors, shapes with dissolving edges, dense, layered compositions with no unifying viewpoint and an unreadable text. Her techniques both create and reflect the intent of the image. The clarity of the hard-edged shapes and bright flat colors in Anasazi Ruins has given way, in Departure, to a more complex and subjective representation of place. Meaning derives not from the fixed viewpoint of objective truth, but rather from a multidimensional landscape in which the interaction of the physical nature of the site and the artist’s experience of the site mingle. Through the assemblage of fragmentary images the artist rejects the right-angled grids and linear timelines which archaeology, anthropology and history use to reconstruct the past into an unbroken, internally consistent and tidy picture. Marcus represents the world instead, through a collection of shifting, contingent and sometimes contradictory viewpoints. The fragmented images focus on the loss and impermanence that characterize any understanding of the past, a loss that carries with it a certain melancholy. Such re-presentations highlight the interpretive role of the artist – the artist as storyteller, as allegorist and the image as a singular expression of a unique experience and viewpoint.

Seen as allegories, Marcus’ tapestries assume a more poetic nature. They go beyond issues of signification to establish relationships, to ponder the unknowable and to express subjective experience. They exist between the symbolic mind and the emotional body, invoking our psychological response to place and especially to the seductive, yet, ultimately unknowable past. Provenance Approximate from 1995 is a dreamlike mélange, in which the dense layering of the image and the scumbled colors echo the stratigraphic layering of an archaeological site, the accumulation of debris and artifacts and the processes of weathering. The title alludes to the fact that all knowledge is contingent and provisional. The layering of the archaeological site is paralled not only in the layered and collaged composition, but also in the process of the weaving itself, in which passes of weft build upon one another in a vertical manner. Not only is the image an allegory of the site, the weaving of the tapestry object can be seen as an allegory of the formation of the site through time.

As Marcus’ interest has shifted away from literal representations of reality, it has also focused more on tapestry as a textile. From more finely woven pieces employing woolen weft, she has shifted to a coarser warp sett and a more diverse range of weft materials. The tactile qualities of the cloth become increasingly important in tapestries such as Dreams of Passage. This emphasis corresponds to what the nineteenth century art historian, Alois Riegl, termed the haptic, derived from a Greek word meaning, to touch. The haptic is opposed to the optic, which refers to sight. Tapestry perches precariously on the fence between the haptic and the optic. Practitioners emphasize the importance of the hand manipulated process and the materials. Yet most tapestry images are firmly rooted in the optic, easily recognized images culled from the surrounding world. For most tapestry artists the medium is not the message.

The duality of optic and haptic is closely connected to the aforementioned opposition of the symbolic mind and the emotional body. Judith Barton speaks of an embodied approach to art making. She believes that materials elicit particular ways of working and that the forms, which result ” constitute the working of our imagination as it engages with the body and senses to structure ideas in the mind and express them publicly in the world.” 4 In Marcus’ recent work, materials and working methods play an increasingly important role as she continues to investigate the notion of site.

In 1997 Marcus was invited to participate in an artists’ retreat in Australia. Situated near the now dry Lake Mungo, artists created work that responded to the local environment. Marcus’ attention focused first on baling wire from an abandoned farm. In addition to photographing the wire on scraps of roofing tin found at the site, she also fashioned studies from purchased wire. Other onsite investigations included plaster gauze castings of local trees and rubbings of the trails of burrowing insects.

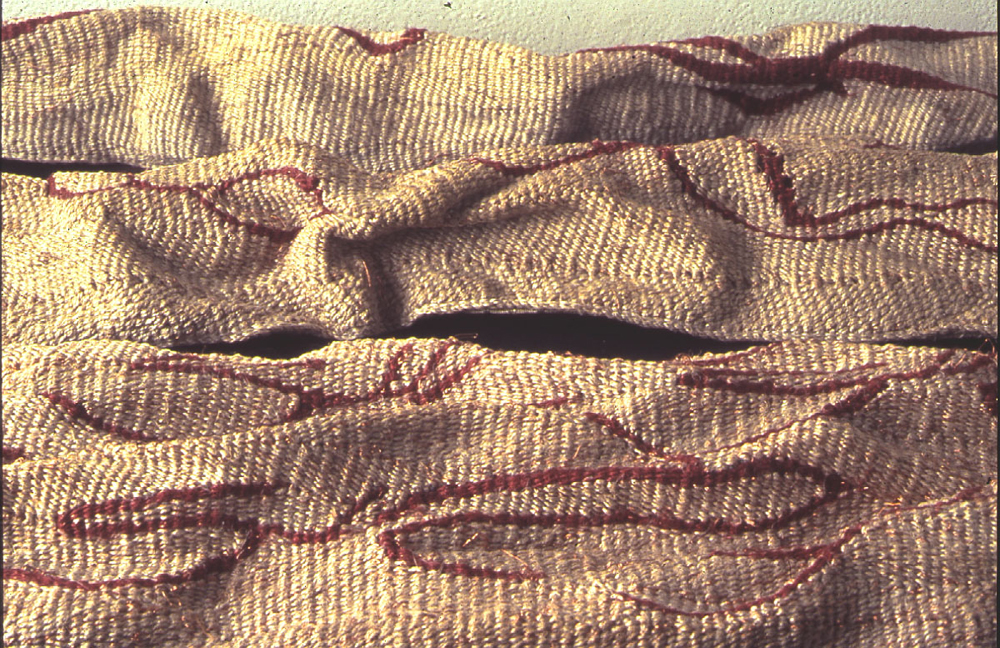

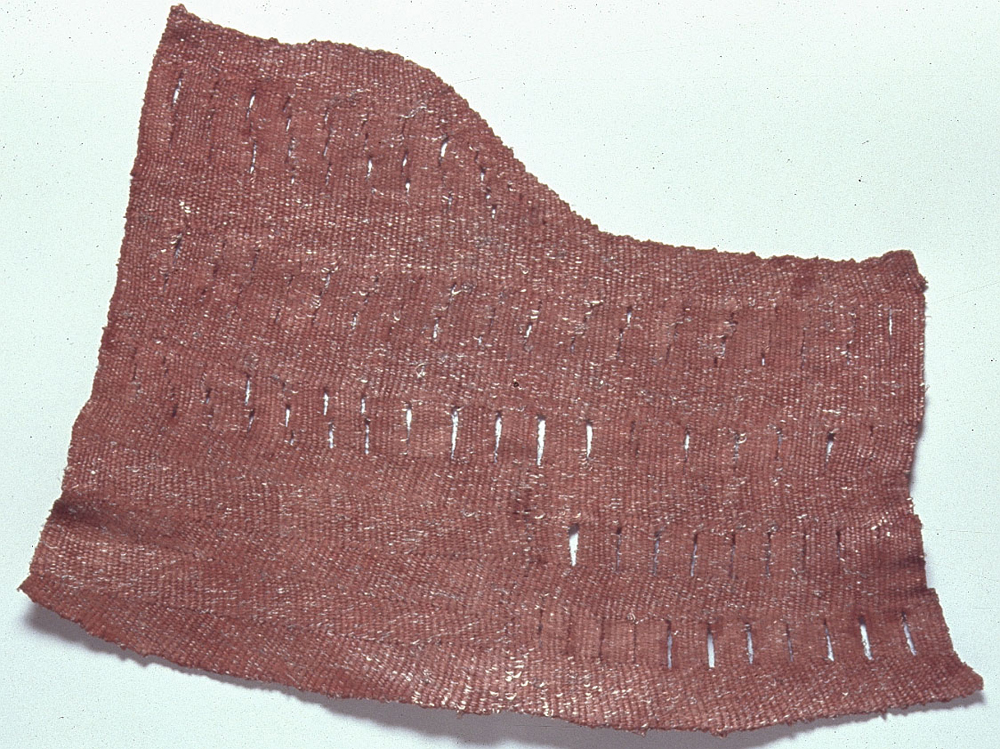

From 1997 to 2001 Marcus developed a body of work that reflected her experiences in Australia and her subsequent reading about the history of that country, especially colonialism and its impact on both the indigenous people and the land. In addition to the woven pieces discussed here, the series also includes prints, artist books and works on paper. Site consists of three linen and wire wedge weave tapestries that are subsequently wetted, stained with tea and then crumpled in order to sculpt them. The red lines in the weaving derive from the images of baling wire that the artist photographed in Australia. The use of linen references the desire by European settlers to grow flax in Australia in order to supply their sail making industry. The use of wire reflects back to the baling wire at Lake Mungo. It also, serendipitously, facilitated the sculpting of the wedge weave fabric. Exhibited lying flat on a platform, the tapestries become metonymic devices for the Australian landscape and, specifically, Marcus’ experience at Lake Mungo.

Site reflects the development of Marcus’ representational style. The increasing abstraction and the significance given to materials and process foreground the evocative and physical nature of the art object over its ability to reference an external world. The pictorial field of the artwork is reduced to the abstract qualities of form, color and line, thereby de-centering the primacy of the subject. Site exists somewhere between representation and artifact. Does this weaving contain an image of land and wire, a reference to an experience in the artist’s past or is it a self-sufficient object existing only in the present? Or is it all of these? Past and present, presentation and re-presentation, figuration and abstraction are all condensed into a conceptual space into which it is difficult to drive any wedge. The conceptual unification of these supposed dichotomies leaves us questioning the nature of their differences.

The meandering lines and texture of the wedge weave in Site suggest stratigrahpic formations. The sensuousness of the undulating surface evokes not only landscape, but also the human body. The wandering red line that originated in the image of baling wire now conjures up the meandering passage of time and the flow of water over land and of blood in the body. The evocative and sensuous nature of this piece offers us an experience not so much of knowing Lake Mungo, but of feeling Lake Mungo through the bodily and emotional associations it invokes.

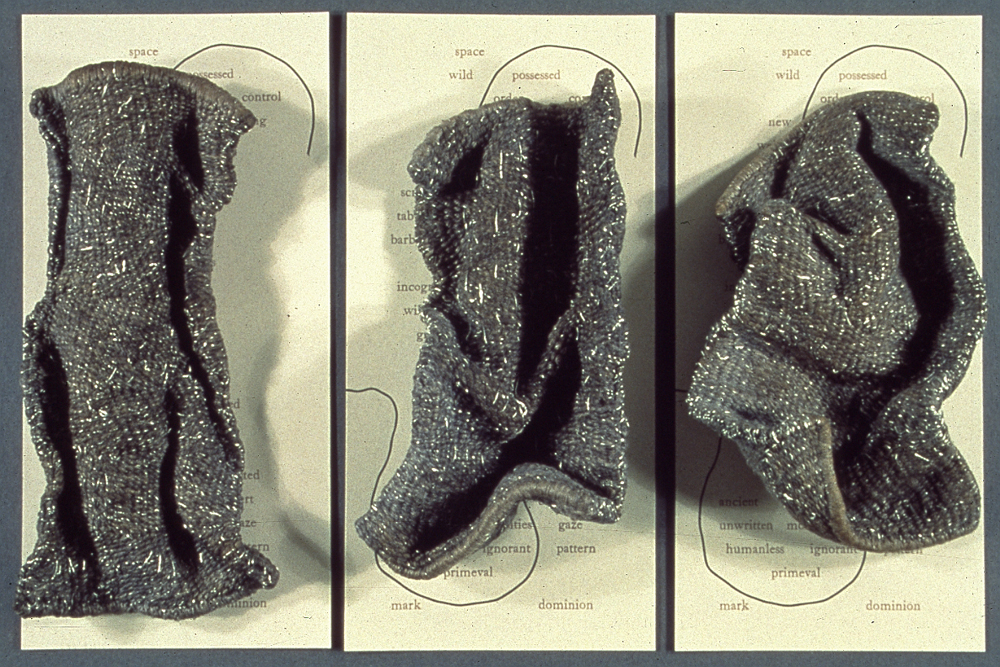

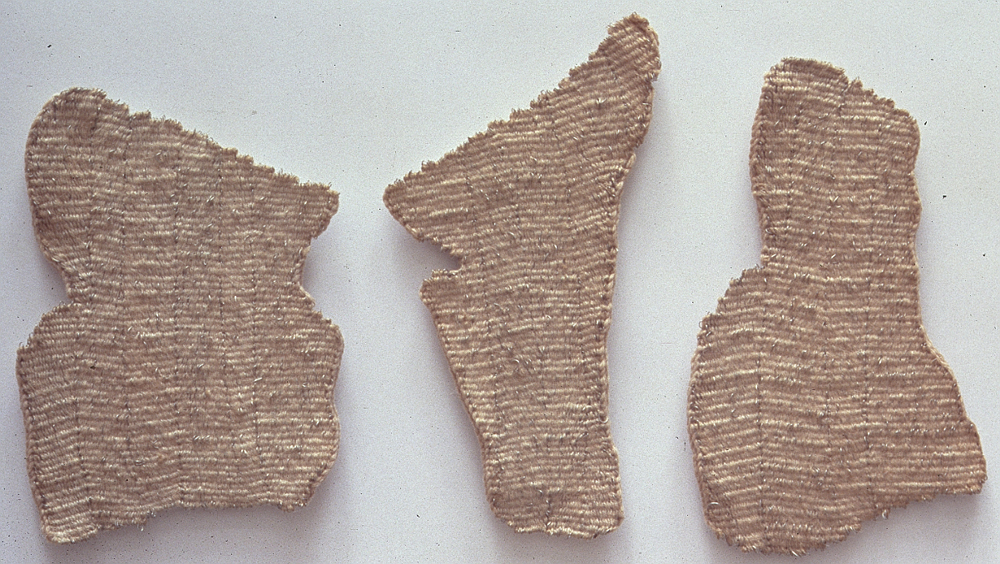

The physical presence of the object continues to be paramount as Marcus continues her exploration in the weavings entitled Chapters 1 through 10, whose making employed techniques similar to those employed in Site. The shaped forms sit atop letterpress cards that contain descriptors for both the indigenous people of Australia and the European colonists. The adjectives are separated by the sinuous line of the baling wire – now symbolic for the control and containment of both land and people that accompanied colonization. These shaped weavings suggest not so much landforms, but charred fragments that remain after a fire or twisted metal thrown off from an accident. They are artifacts. They are also chapters in a story, evidence of the destruction that can result when one culture asserts power over another. The austereness of the object suggests the sorrow and loss contained in the now abandoned site.

The body of work emanating from Lake Mungo exemplifies the artist’s working process. Marcus’ experiences of the site led to her selection of a particular item – the baling wire – which she investigated formally in a series of photographs and then further developed according to her experience as a textile artist with a background in archaeology and anthropology. The re-presentation of the site of Lake Mungo that started with the photos of baling wire and ended with Walls of China, offers the viewer an opportunity to understand the site in a multidimensional way. The multiple perspectives collaged into the earlier tapestries are here individually developed into independent works, which together offer a rich and evocative representation of a place.

Marcus’ digestion of her experience at Lake Mungo continues in Walls of China, the name given to the eroded land formations surrounding the dry lakebed. In Walls of China the outlines of the pieces in Chapters are used as templates for flat wall tapestries. These pieces, despite their reference to landscape, have assumed autonomy as self-contained objects whose reference to the external world is only one part of their meaning. Their fragmentary nature reminds us that we know the past through a mélange of source material, which is both adequate and deficient. They evoke the sense of loss inherent in the passage of time and the power of the imagination to fill those vacant spaces.

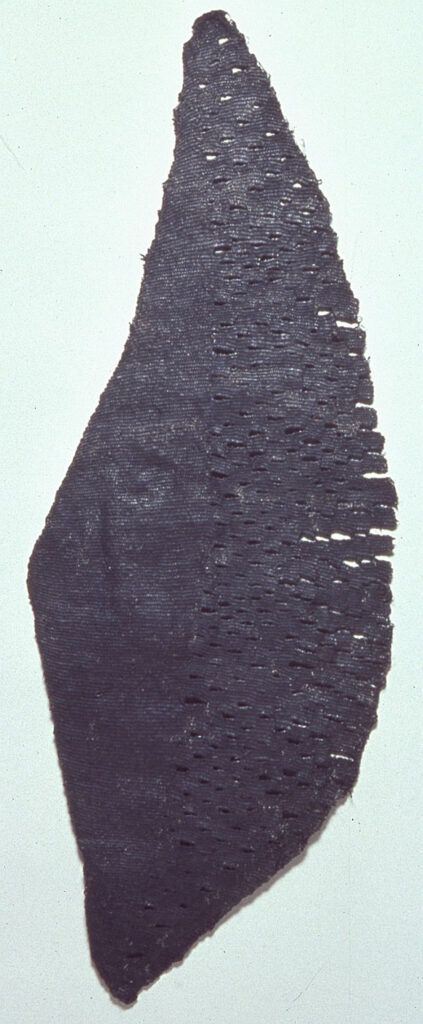

In Marcus’ most recent body of work, entitled Personal Knowledge, the importance of the technical processes and the tendency towards abstraction evident in the Lake Mungo work increases in importance. In Burn, the artist sketches a shape freely on the warp. Using linen and wire for weft, Marcus builds the shape in an intuitive and spontaneous manner, responding to the touch and appearance of the growing fabric. The distorting forces of wedge weave and eccentric weft, the open slits and conventional tapestry joins and surface techniques leave their marks upon the tapestry. The finished weaving is washed, beaten with a hammer to flatten, painted and then burnished. The surface is dense, smooth and stiff. The feel of the fabric evokes tanned animal skin, a deliberate association for Marcus. In Marcus’ words, “[Skin] is a barrier between outside and inside… It is endlessly fascinating for its metaphoric possibilities.” 5 Skin is both a literal and a metaphysical border. It separates the subjectivity of the body from the objectivity of the surrounding world. It mediates between the self and external sensory stimuli. It is conceptually linked to textiles in their role as clothing.

The extended process of weaving, washing, beating, painting and burnishing emphasizes the importance of the action of the artist’s body upon the artwork. Tapestries such as Façade are no longer simply images defined by the logical constraints of the right angles of weaving. These works embody the intuitive and emotional aspects of the artist’s labor upon the woven surface. The intensity with which these tapestries are worked and reworked concentrates their energy and power, resulting in evocative, totemic objects, which assert their autonomy and independence from specific references, suggesting instead, more timeless qualities such as protection and the forces of nature and time on the landscape and on ourselves. These pieces evoke a human presence in their suggestion of worn clothing, aged skin and protective shields. They are not necessarily to be understood intellectually but rather to be felt in relationship to one’s own body and experience. They remind us that knowledge arises out of lived experience.

The evocative nature of Seam elicits an awareness of the self in relation to forces and powers greater than ourselves. The abstracted, suggestive imagery invites the viewer to discover personal meaning in the work. Nancy Princenthal, in her essay on memorials, characterizes these kinds of abstractions in the following manner, “What makes them important is precisely their resistance to easy translation, the mysteries they harbor, their difficulties. Particularity, idiosyncrasy, the quiddity of perceptual experience – these are the best things abstract art can offer…relying not on Minimalism’s psychological recalcitrance but rather on a particularly concentrated emotionalism.” 6 In Marcus’ work, abstraction, fragmentation and the traces left by the working and reworking of the surface evoke larger themes of physical and emotional vulnerability in the face of both natural and human forces, the forces which degrade not only the landscape, but also the memory of people’s lives and culture.

The allegory present in a more literal and narrative form in Marcus’ earlier work is, in Restraint, more symbolic. Allegory’s recovery of the past through retelling and re-presentation becomes here a tale of weathered and fragmentary artifacts whose references are as dense as the pounded and burnished surfaces. These works are metonymic objects that stand in for both the history that has inspired them and the passage of time and forces of nature that act upon those events and the people who lived them. They are examples of what Susan Langer refers to as “the articulate expression of feeling, reflecting the verbally ineffable and, therefore, unknown forms of sentience.” 7

The development of Marcus’ artwork reflects the investigations the artist has conducted into how we know and represent a place. Her skepticism about the objective ideals of scientific inquiry and the hegemony of Western modes of perspectival representation is evident throughout her work. Her re presentation of a site involves an allegorical approach in which the fragmentary nature of historical and archaeological evidence is used to develop a multidimensional understanding built upon subjective experience grounded in the body. As textiles these pieces evoke the cultural associations of cloth and fiber and the processes of their making. In the hands of the artist those associations are exploited in the service of both intellectual and emotional concepts. It is the fusion of the conceptual intent with the processes and materials of the medium that lends particular significance to Sharon Marcus’ work.

Marcus’ interest in the past reflects not only her exploration of how we know and represent the world, but also her belief that the past holds meaning that is relevant to the present. Such a viewpoint questions Modernism’s eternal search for the unique, its insistence that all promise and potential lies in the future and its notion of progress as necessarily positive.

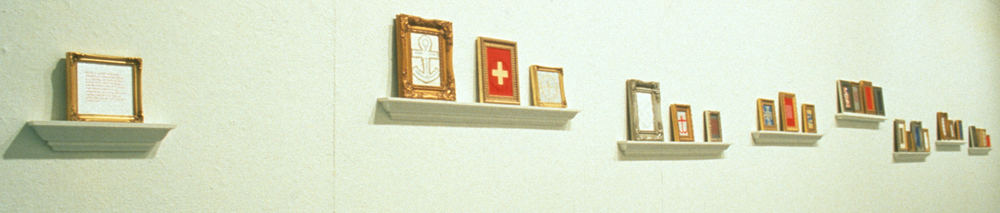

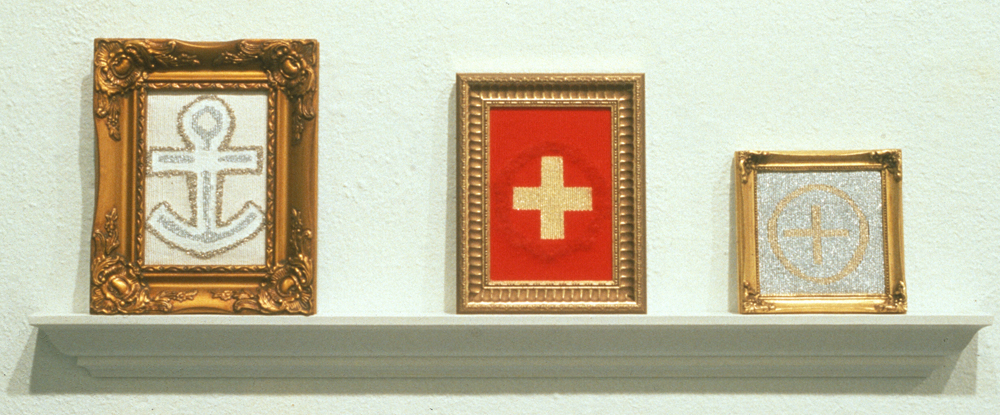

In 1996 Marcus embarked on a multi piece project entitled Ornament. Although the hard-edged shapes and primary colors that dominate in these works seem antithetical to the tapestries we have just seen, it will soon become apparent how closely they are linked. The twenty-five pieces that comprise this work include images of crosses, swastikas, camouflage cloth and maps and text that are either woven or screen-printed and subsequently mounted in ornate wooden frames. 3 The concept behind the work grew out of Marcus’ interest in pattern and ornament, and the ways in which an ornamental device, such as a cross, can become a powerful cultural signifier. Through time the meaning ascribed to such a symbol can change and symbols may harbor multiple, even contradictory meanings. Ornament combines the cross, normally associated with the benevolent teachings of Christ; with computer generated patterns developed from maps indicating the location of hate group organizations within the United States. Through the artist’s stylistic choice of hard-edged forms and strongly contrasting colors, she exposes the black and white thinking that underlies the morally charged agenda of such groups. This kind of thinking and representation is diametrically opposed to the more complex and shifting view of the world presented in tapestries such as Departure (and the pieces discussed earlier). Marcus’ intention is to point out the ways in which common symbols can embody multiple, and sometimes contradictory messages. The artist states, “In a complex universe of such “ornament” we are all well advised to look beneath the surface.” 4

End Notes

1. Kim Stafford “An Intricacy of Means” Haystack Monograph

2. David Hockney has explored extensively methods of perspective and representation and how they relate to human perception. His use of photographic collages in the Cameraworks pieces explores these issues. See That’s the Way I See It. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1993.

3. Owens, Craig. Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

4. Burton, Judith M. “Materials and the Embodiment of Meaning” in Crafts and Education: Haystack Monograph 1999. Deer Isle, Maine: Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 1999.

5. Marcus, Sharon. Artist’s Statement. November 3, 2003

6. Princenthal, Nancy. “Absence Visible.” Art in America April 2004.

7. Langer, Susan. Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953.