This exhibition review was first published in the Surface Design Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1

Archaeologies: Structures of Time

Contemporary Craft Gallery , Portland, OR, 1995

United by their common experience as archaeologists, Diana Wood Conroy and Sharon Marcus have mounted a show of tapestries and drawings that engage many concerns of the late 20th century. The work of both artists elaborates the notion of site – the physical place in which a culture sat, ate, and died. For Wood Conroy, the representation of site is a meticulously rendered drawing or weaving based on aboriginal middens and burial sites in Australia, her homeland. In Marcus’ tapestries, fragments of geographically and chronologically disparate locations are fused by the use of repetition, disjunction and overlays.

The inherent tension between the chaos of the physical remains that confront an excavator and archaeology’s systematic relationship to human history activates the images. In Wood Conroy’s work, this is built through the use of the grid, the rectilinear string graph placed over a site in order to establish the reference system for the materials unearthed. In Her only desire: fragmentary site with Lady from Palmyra, the grid is a strong presence that lies between us and the artist’s representation of the site. It prevents a direct experience of the underlying ground, forcing us to channel our perception through the square matrix. However, in Black Ground, Ballambi, the grid is elusive and our experience is visceral, emphasizing the material itself and not the order that archaeology might eventually impose upon it. This dichotomy of ordering chaos is also confronted in Wood Conroy’s work by the juxtaposition of classical references, the ultimate legitimation of the western world and the foundation of her professional training, with the physical sites of aboriginal Australia, the indigenous history that colonial Australia has neglected for so many years. It reaches an especially haunting climax in Ground, Lake Mungo, in which a tapestry fragment depicting the pelvis of a pregnant woman is placed upon a drawing of the site at Lake Mungo. The skeletal remains, although a western artifact, refuse to acknowledge the cultural differences commonly emphasized in the human sciences, forcing attention instead on our common fate. The striking contrast between the rigidity of the woven image, which assumes an iconic role, and the fluidity of the drawing further heightens the tension between science and experience.

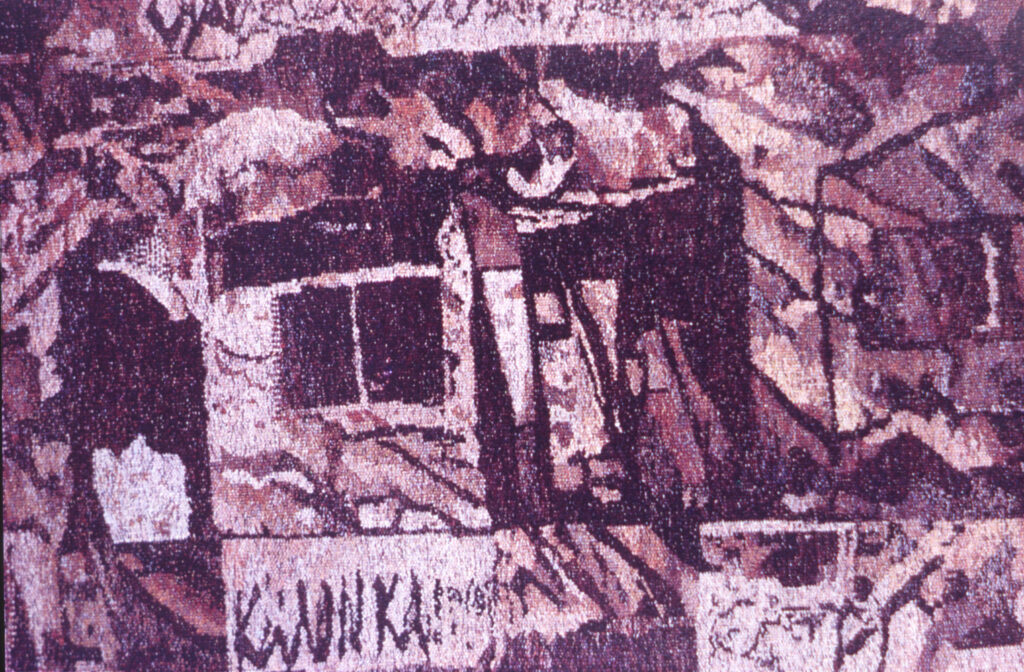

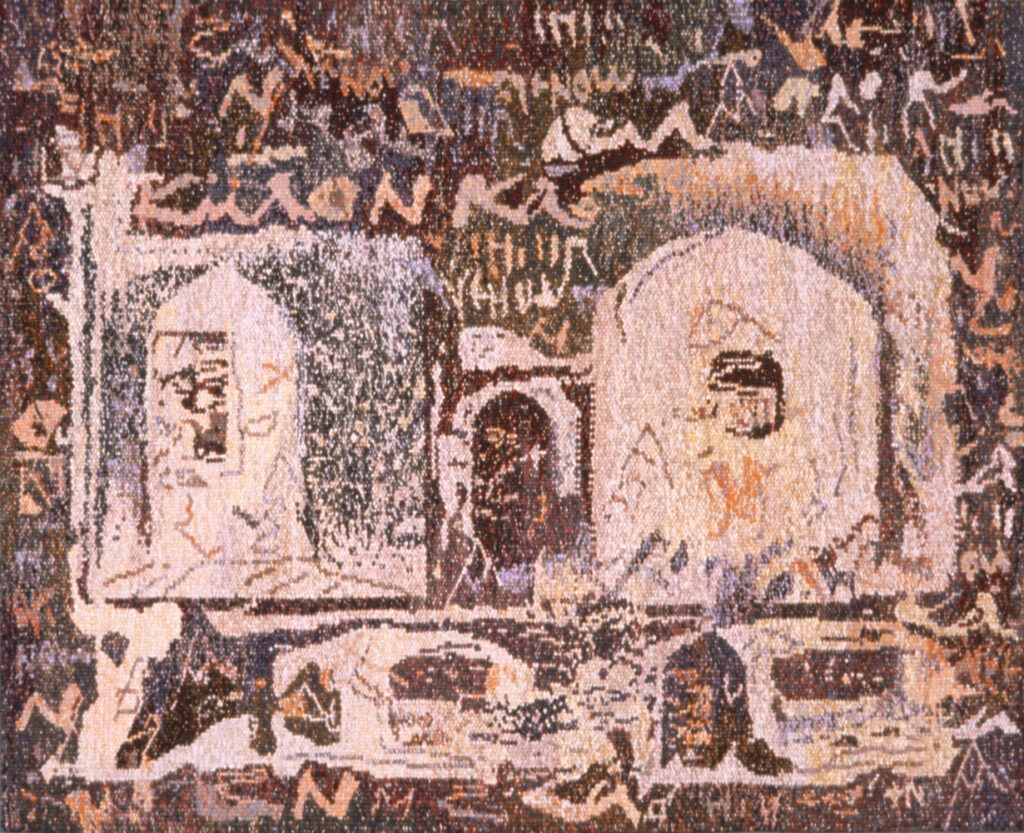

Marcus’ tapestries offer a direct, tangible encounter. They invite us to experience the shifting, enigmatic nature of perception. Fragments of time and place defy the rationality of science, fusing into a multidimensional reality Marcus refers to as “intangible an ambiguous.” In Excavating Santana our impressions of architecture and space are confounded by the intense barrage of information presented. This tactic encourages not a topographical reading fixed in time, but a multisensory reading in which space and time lose their ontological status. Marcus negotiates this experience through the use of borders, a device normally employed to create a barrier between a work of art and the rest of the world, establishing the art as autonomous and self referential. However, in the tapestry Departures, the borders are incapable of holding back the materiality of the site. That creeps out, slightly modified, to assert its identity over the impartiality of the border by distorting its rectilinearity. This subversion of the border also suggests a continuity in which art and life mingle.

The tension between order and chaos, intellect and materiality, Western and non-Western culture developed in the work of Wood Conroy and Marcus finds direct parallels in current linguistic and feminist theory. Rather than offering inviolable truths, the work examines the means by which experience and perception become codified into knowledge. It presents knowledge as constructed, as a product of culture and symbolic language imposed upon the shifting and amorphous materiality of experience. The use of barely discernible text in Marcus’ Treasure the Dream alludes to the joint program of image and language by invoking ancient hieroglyphic picture writing. The plurality of the exhibition’s title, Archaeologies: Structures of Time, also suggests that there is not one truth but rather that experience is mediated to the web of culture and is therefore relative and unstable.

The position of Wood Conroy and Marcus as interpreters of the past links their work to an allegorical program. Allegory is always, in some sense, an attempt to fix the past from potential loss in cultural memory and as such, it often carries with it a sense of melancholy. This concern In Wood Conroy’s work is expressed through her attempt to document, in essence to memorialize, the aboriginal past, which she muses may be “unrecoverable.” It is reflected in both artists’ work through an obsession with the fragment, the eroded physical remains of a people, and with the use of appropriated imagery. Appropriation honors what is borrowed, yet its use necessarily entails reinterpretation. For the allegorical act of doubling fixes the borrowed image in the past while our understanding springs from the cultural milieu of the present. Thus the artist’s attempts to piece together fragments in order to rediscover meaning both invite and trouble are reading of the image, for, as Wood Conroy tells us, “the absences within the site… are as dominant as the presences which are never complete.” It is, perhaps, this tension built between the past and the present, between the rationality of archaeology and the chaos of the site, between knowledge and experience, that remains one of the most compelling memories of the show.