This article was first published in Tapestry Topics, Vol _, No. _

aesthetics

1 a set of principles concerned with the nature of beauty, especially in art.

2 the branch of philosophy which deals with questions of beauty and artistic taste. 1

The concepts behind the word aesthetics have a long history. Plato’s writings launched a theoretical consideration of beauty long before the German philosopher Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten coined the term, aesthetics, in the 18th century. Despite the incredible complexity of this field, my focus in this short paper will be an illustration, through tapestry, of Arthur Danto’s discussion of the two concepts, “artistic beauty” and “aesthetic beauty.” 2

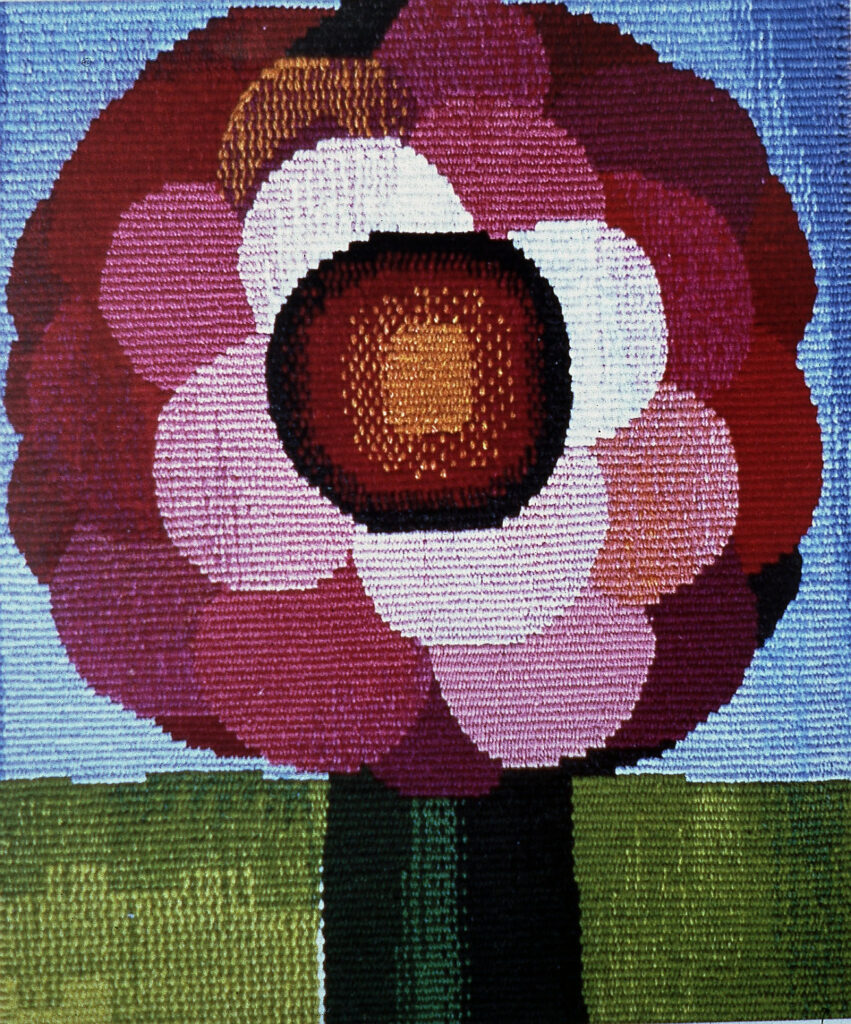

Aesthetic beauty refers to what most of us think of when we hear the word beauty. It could easily be applied to tapestries such as Mary Lynn O’ Shea’s Three Iris, in which the artist’s technical prowess conveys the incredible voluptuousness and sensuality of the flower that many of us associate with our grandmothers. Aesthetic beauty in both art and nature has been widely admired and has even been considered to possess a kind of moral truth. This latter attribute relates to art’s ability to elicit an elevated awareness of universal principles.

Throughout the 20th century, however, many artists lost interest in the kind of aesthetic beauty celebrated in Three Irises. Artists in the early twentieth century witnessed their society engaged in the unspeakable cruelties of two world wars and asked themselves how, in such a climate, they could embrace the pursuit of beauty. Many artists chose to address their political and social concerns through traditional artistic media, including Pablo Picasso, whose mural, Guernica, was painted as a reaction to Franco’s decimation of a small Basque village and remains one of the strongest artistic indictments against war.

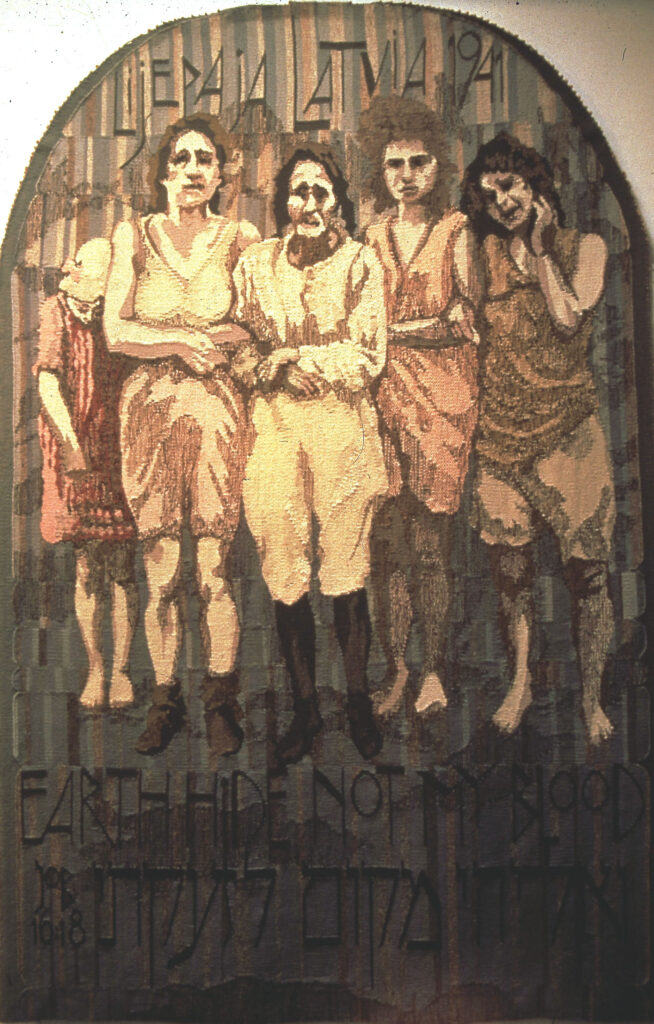

Muriel Nezhnie’s tapestry, Daughters of Earth, focuses on a different genocide. It documents, through a simple, photojournalistic style, the atrocities of the Holocaust. The stark image rendered in gray tones leaves no space for equivocal responses. It invokes the kind of pain and emptiness one feels in the midst of overwhelming events. Nezhnie’s tapestry reminds us to act in the present in a way that precludes such events from ever occurring again.

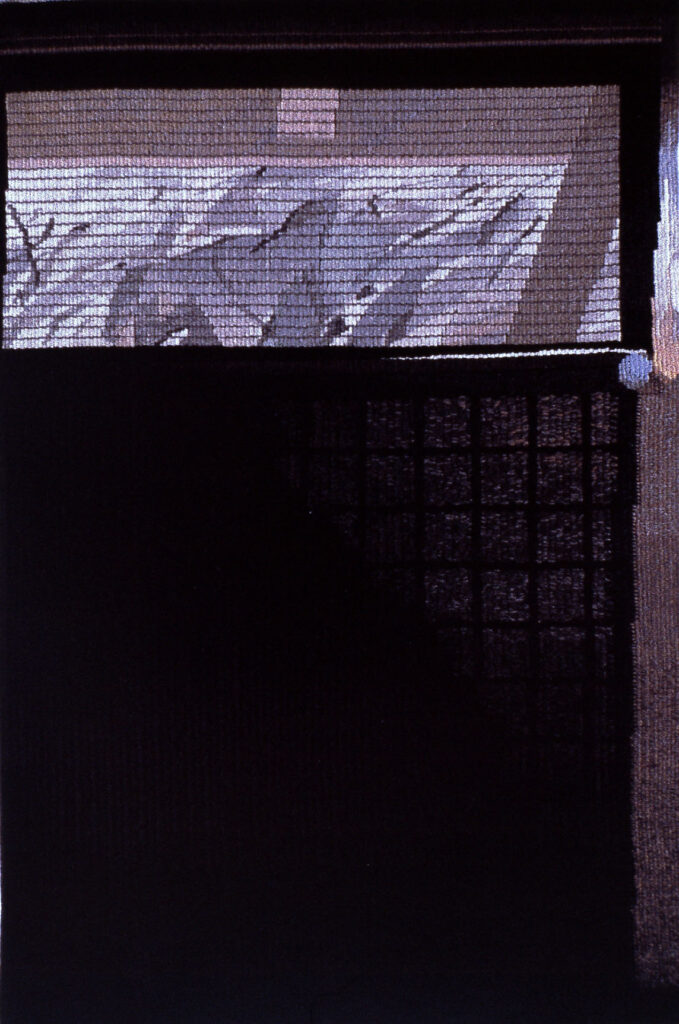

In Kay Lawrence’s suite of tapestries, A Walk Around of the Inside Looking Out, the artist approaches social issues in a metaphorical and poetic style. Lawrence’s representation of the shadowed recesses of domesticity that define many women’s lives suggests both comfort and constraint. The sober colors and strong contrast allude to the clear and often inviolable distinction between our public and private lives. Such dualities and contradictions characterize women’s social position.

The term aesthetic beauty, in the sense of O’Shea’s Three Irises, might be difficult to apply to works such as Guernica, Daughters of Earth and even A Walk Around of the Inside Looking Out. For art that expresses itself with methods other than aesthetic beauty, Danto invokes the concept of “artistic beauty”. Artistic beauty refers to qualities intrinsic to the artwork that are responsible for its meaning and effect. These qualities may involve attributes other than aesthetic beauty, for example, the anger displayed in Guernica, the sadness and horror elicited by Daughters of the Earth or the melancholy of A Walk Around of the Inside Looking Out. In this kind of thinking art possesses content and the artist employs a variety of means to communicate that content to the viewer. If we call these works beautiful, we are not necessarily referring to the kind of beauty manifested in a field of flowers or a quiet stream. We are referring instead to the beauty associated with artistic expression of a more conceptual nature and particularly with art which displays an exceptionally fine fit between the artist’s means and the artist’s message.

At the same time that certain artists turned their attention to political and social issues, other artists focused their work on philosophical concerns. The questions concerning the nature of art and the identity of the artist raised by Marcel Duchamp’s, Fountain, are still being explored, and debated. One of these questions regards the distinction between high and low art, which Leonie Besant raises in her cheeky celebration of the decorative, Stick your Aesthetic Where it Fits. Her childlike rendering in strongly contrasting colors may seem overly simple, but what about Marimekko textiles or Gee’s Bend quilts? How shall we classify those objects?

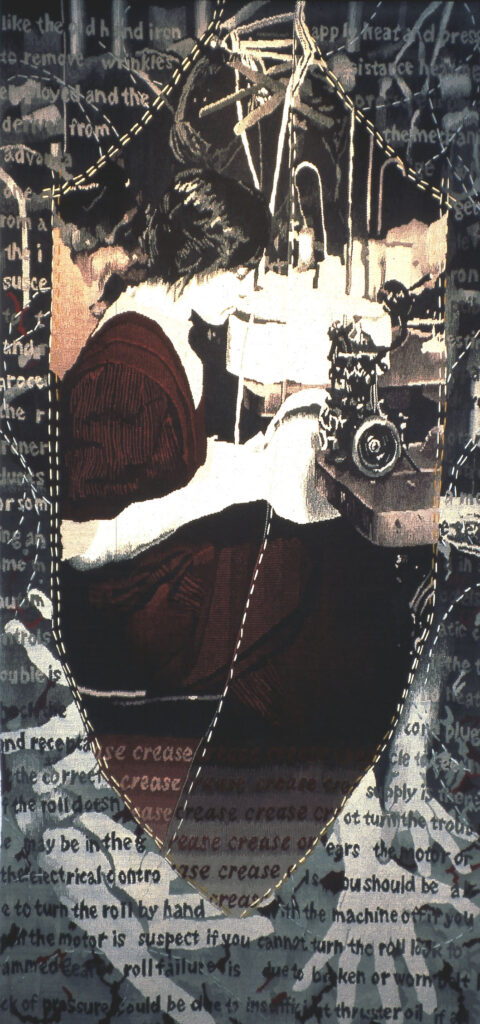

Another philosophical question concerns the role of the artist and the nature of creativity. The use of found images, such as those employed in the design of Shelley Socolofsky’s, Crease, permeates much of what is called postmodern art. Appropriation decentralizes the traditional artistic skills of drawing and painting, essentially redefining creativity. The artist is transformed from alchemist to scavenger.

In light of the changing attitudes that characterize late twentieth century art, Danto considers whether aesthetic beauty can be a valid strategy for contemporary artists. His answer is unabashedly positive. Danto believes that, despite the cultural specificity of what might be considered beautiful, the concept of beauty itself is universal and a fundamental human value. Aesthetic beauty, like its more conceptual, political or philosophical cousins can be an effective strategy in art, one of a number of tools that adds to the artistic beauty of the work.

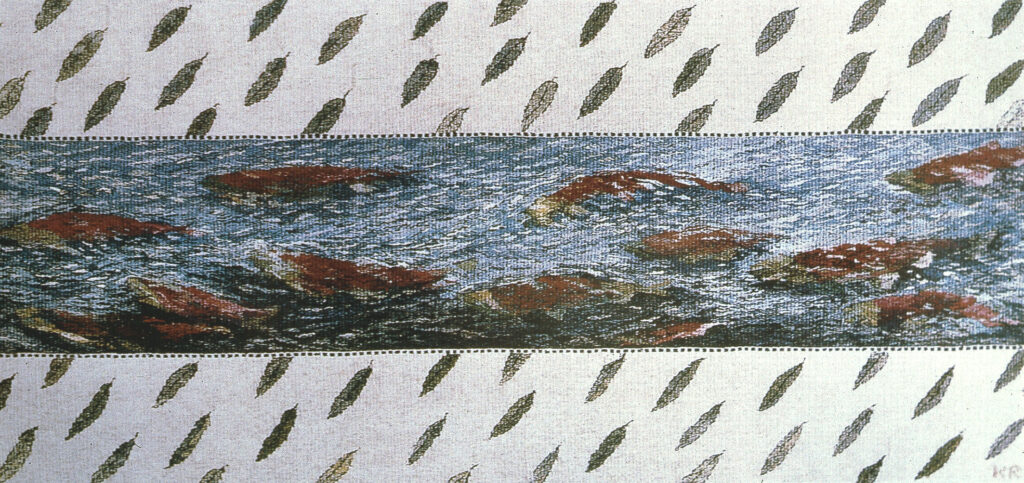

Aesthetic beauty describes Kaija Rautiainen’s tapestry, Salmon Stream. Her sensitive handling of materials highlights their sensuousness and the subtle beauty of the image displays a reverence towards the subject. However, the work also possesses a political edge. It portends the potential destruction of fragile ecosystems when management decisions are based solely on economic values. Rautiainen’s successful integration of beauty and content makes Salmon Stream an especially compelling image.

What distinguishes artistic greatness if the notion of artistic beauty has opened the floodgates to an “anything goes” kind of attitude? Danto would answer, I believe, with a quote from the philosopher G.W.F. Hegel that he often invokes. Great art, Hegel said, is “born of the spirit and born again.” Danto interprets this as meaning that an idea is born in the mind of the artist, then born again in the making of the art object and finally born once more through the experience of the viewer. Within this concept of greatness Danto believes that art can offer a transformative experience by addressing the human spirit and the values that elevate human experience. In the words of Dave Ferrera, “Art can do what no mathematical equation can, what no string of premises and conclusions has ever come close to – it can speak the unspeakable, express, the inexpressible and make visible with perfect clarity the dimmest truth in a world engulfed in darkness.” 3

End notes

1 Ask Oxford, http://www.askoxford.com/?view=uk

2 Danto, Arthur. The Abuse of Beauty: Aesthetics and the Concept of Art. Chicago: Open Court, 2003

3 Ferrera, Dave. “Painting Morality.” Phirebrush Release 25 http://www.phirebrush.com/articles.php?article=04