“A Piece of String” was first published in the catalog for the 2003 show Contemporary Tapestry: Archie Brennan, Susan Martin Maffei, held at the New Jersey Center for Visual Arts in Summit, New Jersey.

Consider string – a twisted thread. Wool, cotton or linen fiber spun into a spiraling, sinuous line possessing dimension, weight and gravity. The technology of fiber is one of the oldest, producing objects both useful and aesthetic. The methods of manipulating spun thread are vast. Tapestry weaving is but one of those techniques – a simple system of interlacement in which the one set of threads (the warp) is stretched tightly on a frame (the loom) and a second set of threads (the weft) passes perpendicularly through the first set alternately under, then over each consecutive thread.

It is the medium of tapestry weaving that Archie Brennan and Susan Martin Maffei have chosen as their means of expression, considering it not simply as a format for representational imagery, but as a rich vein of possibilities to be mined for its inherent power, as a visual and structural language whose insistent and compelling nuances must be internalized so that the medium and the artist speak as one.

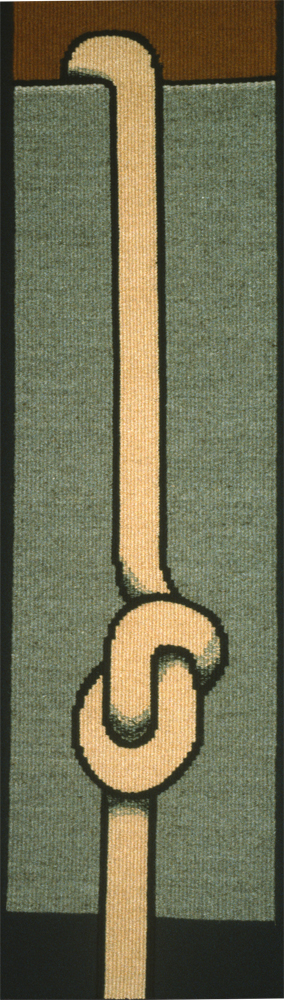

Brennan depicts literally, in Knot II, a knotted thread. The image conveys the tension, the movement, the arrested flow and the weight of the thick, hitched cord. The verticality of the rope and the implied pull of gravity evoke the qualities of tapestry, a cloth which hangs and drapes under its own weight. Brennan creates an image which contains a dialogue between the depiction of thread and the actual thread of the tapestry. This kind of meta image, which contemplates its own making, is common in Brennan’s work and reveals his thoughtful and provocative approach.

Verticality and weight are implicit in the subject matter of much of Brennan’s work, the human form. In Portiere/ Portiere the kimono spills onto the floor in stiff, Byzantine like folds, anchoring the woman’s body to a rug which transfigures the lines of the kimono into an interlock pattern. The edges of the rug defy spatial recession by refusing to converge, tipping the plane of the floor vertically so that it is coincident with the surface of the tapestry. Spatial ambiguity marks much of Brennan’s work. The artist’s juxtaposition of the flat patterning on the rug and wall paper with the three dimensional body, itself simply an assemblage of flat shapes and forms arranged in such a way to suggest overlapping planes, points out the conventional nature of representational modes. The presentation of conflicting spatial relationships in the image calls attention to the methods of the artist and reminds us that the image is not a transparent window onto reality. The image is simply a piece of cloth composed of individually woven, colored shapes arranged according to a set of conventions chosen and manipulated by the artist for a specific purpose.

Grids appear in much of Brennan’s work, and especially in the large body of work referred to as the Drawing Series. Grids are fundamental to woven tapestry. The two linear sets of threads, the warp and weft, interlace in a perpendicular fashion, row by row, creating a grid in which only the horizontal, colored wefts are visible. The tapestry grows from one end to the other, in a sequential and methodical process. The image created can be altered only by unraveling and reweaving.

Grids can be used as a drawing tool which aids in converting the three dimensional world into a two dimensional drawing that most would describe as “realistic.” Brennan incorporates the grid directly into his images, not to clarify space, however, but to confuse it. In pieces such as Drawing Series XXXIX and Drawing Series XVII, straight and angled lines divide the background into a series of flat, geometric spaces which lie both in front of, and behind the figure, complicating our reading of the body in space. Instead of providing a cohesive spatial environment, Brennan employs the grid to trouble accepted conventions of perspective.

In Drawing Series VII, 1st version the thickness of the contour lines and the high value contrast between the lines and the background highlight the vertical warp threads, stating clearly that this image is a weaving. The line, which in the drawing resulted from one fluid hand motion becomes, in the tapestry, a deliberate and measured series of steps whose length and width are determined by the spacing of the warp and the thickness of the weft. The solid blocks of color in the tapestry celebrate their geometric form more than their function as shadows. Illusion is not the point. Rather, Brennan creates, in his work, a dialogue between the image, the techniques of tapestry and the conventions of representation, allowing the power to shift subtly from one component to another.

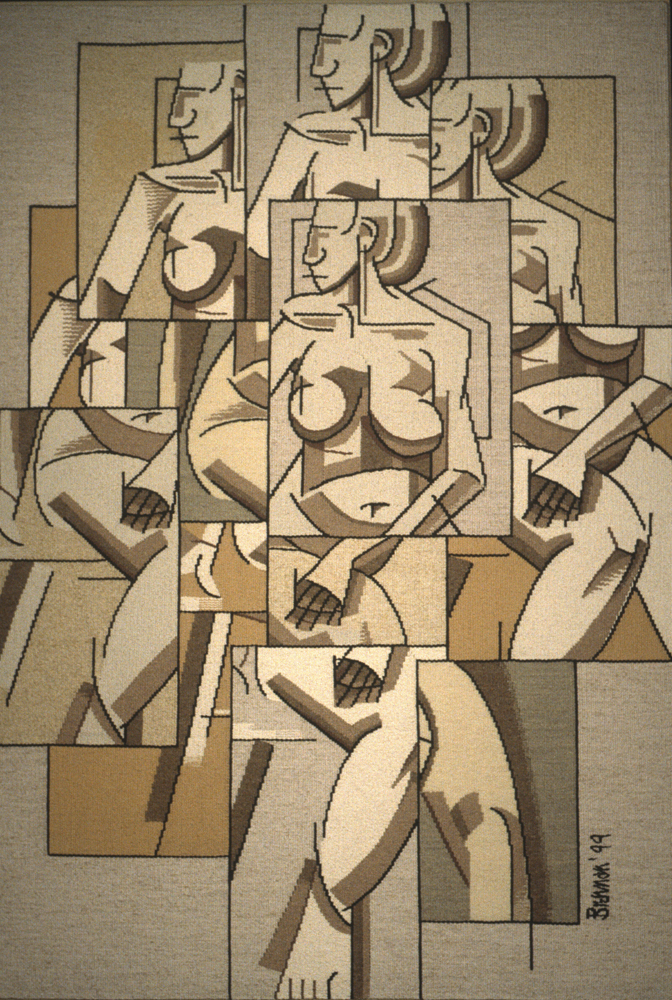

(right) Archie Brennan, Seated Nude, Seated, Seated, 50″ x 34.5,” photo: Archie Brennan

In Drawing Series XXXIII and Seated Nude, Seated Nude, Seated the grid overpowers the figure, shattering it into pieces, which are shifted, multiplied and deleted, leaving us with a collage of deconstructed body fragments that show little concern for the integrity of the human body. The grid in Drawing Series XXIX literally breaks apart the image into twelve, physically separate units.

Brennan’s use of the grid as a compositional device intersects with another one of his interests, mail art. Twelve Postcards is an example of a piece whose separate parts were mailed to the exhibiting gallery. For this show, 72 postcards mailed from points around the world combine to form the ambitious A World Map. The image derives from a JAL map Brennan found in the airline’s magazine. For an active mind like Brennan’s, found material becomes thought provoking. The map, which shows the world from an uncommon perspective – the North Pole is in the middle of the map – illustrates how our understanding of the world depends on the way in which it is represented. Like his inquiries into the representation of the human body, this piece points out the arbitrary nature of representational conventions and the power they have over our interpretation of the world.

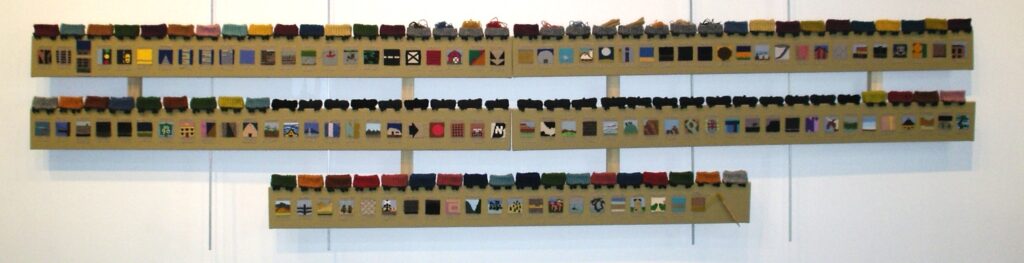

Susan Martin Maffei shares, along with Brennan, an interest in foregrounding the process of weaving through her images. In Road to Haleakala the path of the road winding up the mountainside is coincident with the weaving of the tapestry from the bottom edge to the top. The subject matter mirrors the process. In Sketches – New York to Mendocino, a series of miniatures documents the artist’s journey across the country on a train and in Tolovana Beach Walk the viewer follows Maffei’s steps along a stretch of the Oregon coast. The making of these tapestries, and our reading of them, unfurls like a scroll, paralleling the artist’s actual journey through time and space.

Maffei’s extensive study of, and respect for, historic European and pre Colombian tapestries has resulted in a style in which shape predominates over line. Her emphasis on representing the world as a collection of distinct forms also reflects the process of tapestry weaving, in which each color is built independently. In The Audience and Traffic, the individual figures and cars within the images form a pattern distinguished by alternating colors. Maffei uses pattern extensively in her work. Her patterns are not, however, symmetrical, or regular and the shapes are not abstract. Her interest is not in distilling her observations into essences, but rather in celebrating the individuality and idiosyncrasies of the people and the world around her. Nowhere is this clearer than in the tapestries Home, Money and Business and Travel, where the accumulation of numerous lively details enriches our understanding of the subject’s personality.

(right) Susan Martin Maffei, New York Times Series: Home, Money & Business, 85″ x 30,” photo: Susan Martin Maffei

In Home, Money and Business, part of the impressive New York Times Series, Maffei presents a chaotic kitchen scene filled with the clutter of life. The depiction, however, is not photographic. It is filtered through her obvious delight in detail, color and pattern and a playful manipulation of space. The movement and distortion of the shapes in the little boy’s shirt and the high chair cover create the illusion of three dimensions. The floor tiles, however, maintain a constant shape, thus denying the three dimensional space of the room and tipping the floor plane up to join the flat surface of the tapestry. The window offers yet another perspective as it opens onto a view outside the room. The artist’s combination of viewing perspectives allows her to present each part of the image in the way which best describes it, much as the mixture of frontal and profile aspects in African sculpture does. The combination of perspectives calls attention to the power of the artist in constructing the image and influencing our understanding of that which is depicted. This approach, combined with the strongly colored, pattern based detail reminds us that her image is part of a long tradition of tapestry weaving in which color and form take precedent over seamless, illusionistic renderings.

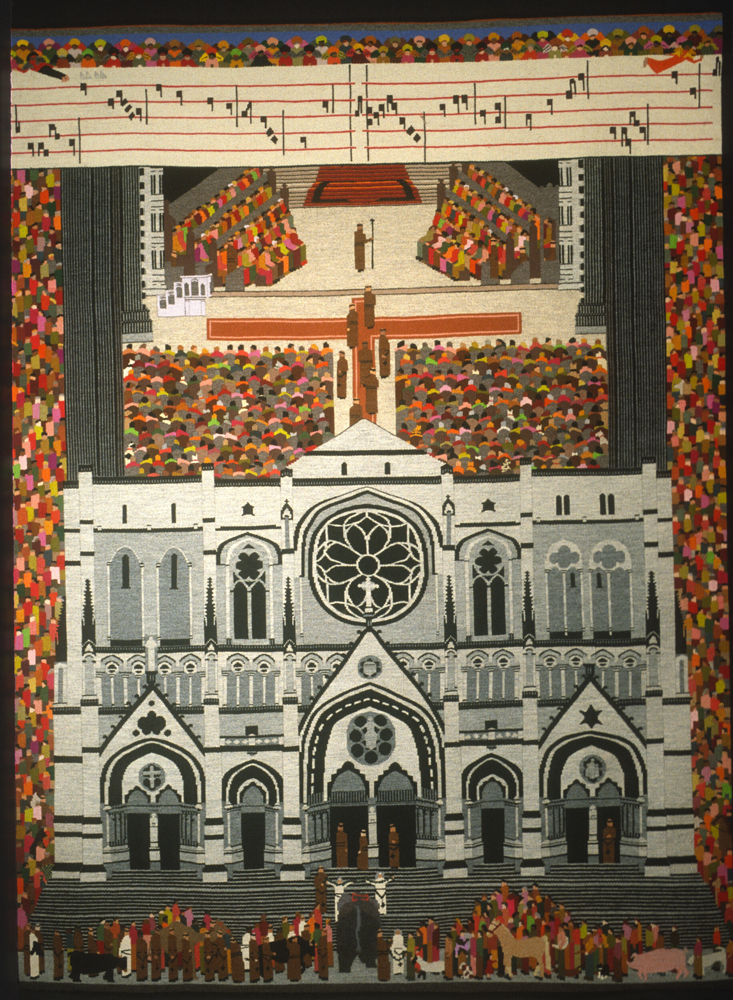

The artistic force operating behind the New York Times Series comes to a crescendo in Blessing of the Animals, Maffei’s rendering of the annual event at St. John the Divine Cathedral in Manhattan. The parade of people and animals winds around the church, forming a border along the edges and finally arriving at the Gothic facade, which is depicted frontally. The interior of the church is presented from a bird’s eye view and the rows of the choir converge into the nave. The antiphonal music is represented by a flat banner which spans the width of the tapestry, breaking apart the seemingly endless throng of people streaming into the church. The stark, geometric black and white of the church contrasts with the lively, colorful and more irregular patchwork of people and animals.

photo: Susan Martin Maffei

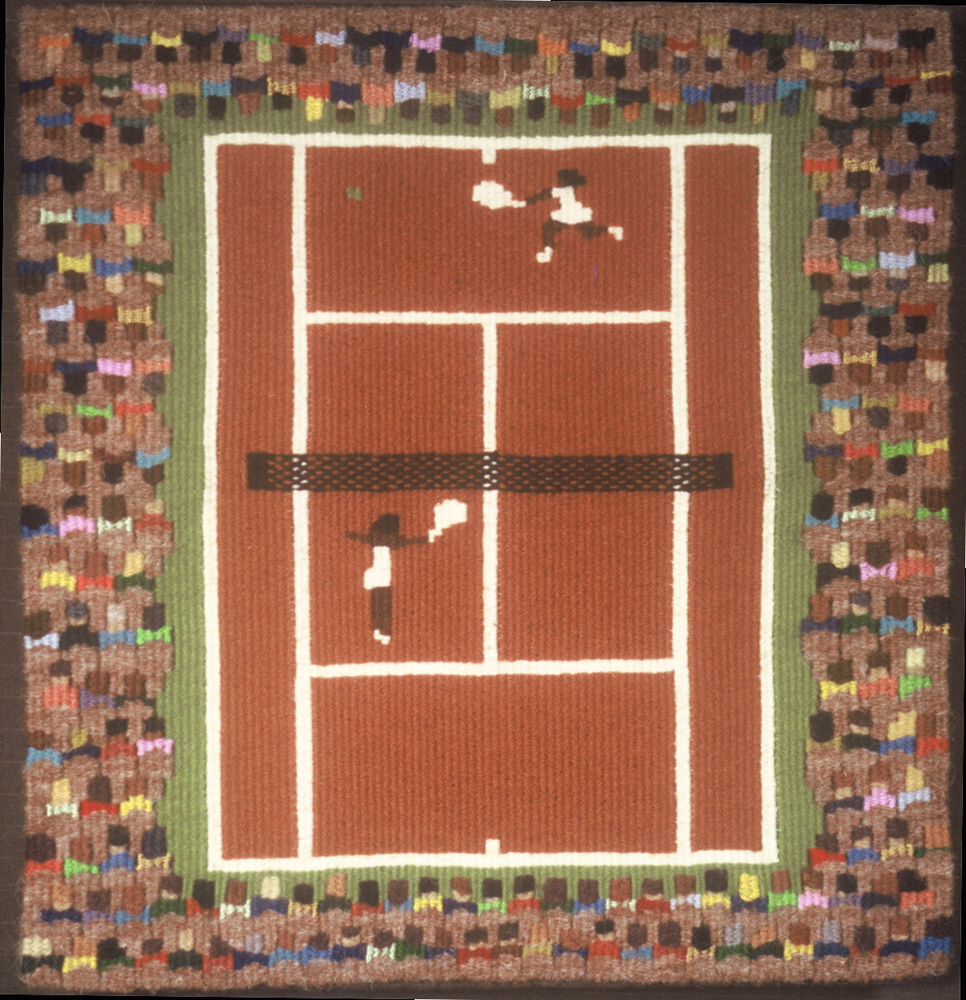

Recently, Maffei’s attention has been drawn to sports. She represents the courts and fields in grid based patterns reminiscent of checked and plaid fabric. The players assume action poses and the spectators merge in a playful intermingling of color and pattern. In French Open Maffei again combines different viewing perspectives. The court is seen from a bird’s eye view but Venus and Serena are seen as though one were sitting in the audience along the bottom of the tapestry. The audience is presented from two different perspectives, half as though the viewer were sitting at the bottom of the tapestry and half as though the viewer were sitting at the top. The bodies shift direction mid way through the piece.

In Golf – The 17th Hole the weaving of the tapestry follows the progression of a foursome playing a hole of golf, starting at the tee, following the players down the fairway, out of the sand trap and finally onto the green. The mowed grass and the surrounding vegetation create woven patterns, the movement of the water forms a series of undulating lines and the tiny colorful figures, each defined by only two warp threads, stand behind the red rope that snakes its way along the length of the 17th hole. Maffei develops the narrative as she weaves the tapestry, using little in the way of drawings, instead allowing the image to develop within the language of the cloth.

The tapestries of Susan Martin Maffei and Archie Brennan are a testament to the dedication of two thoughtful and inventive artists. Their explorations into image making and the conventions of representation remain in constant dialogue with the physical qualities of thread and the structural realities of the tapestry weave construction. For both, maintaining that dialog as an open question, rather than claiming an authoritative answer, keeps the work fresh and diverse. Viewers are rewarded with provocative, witty and creatively idiosyncratic works with both aesthetic and intellectual content.