This article, without the entire suite of images, was first published in the International Tapestry Journal, Vol. 2, No. 1.

Dersu Uzala

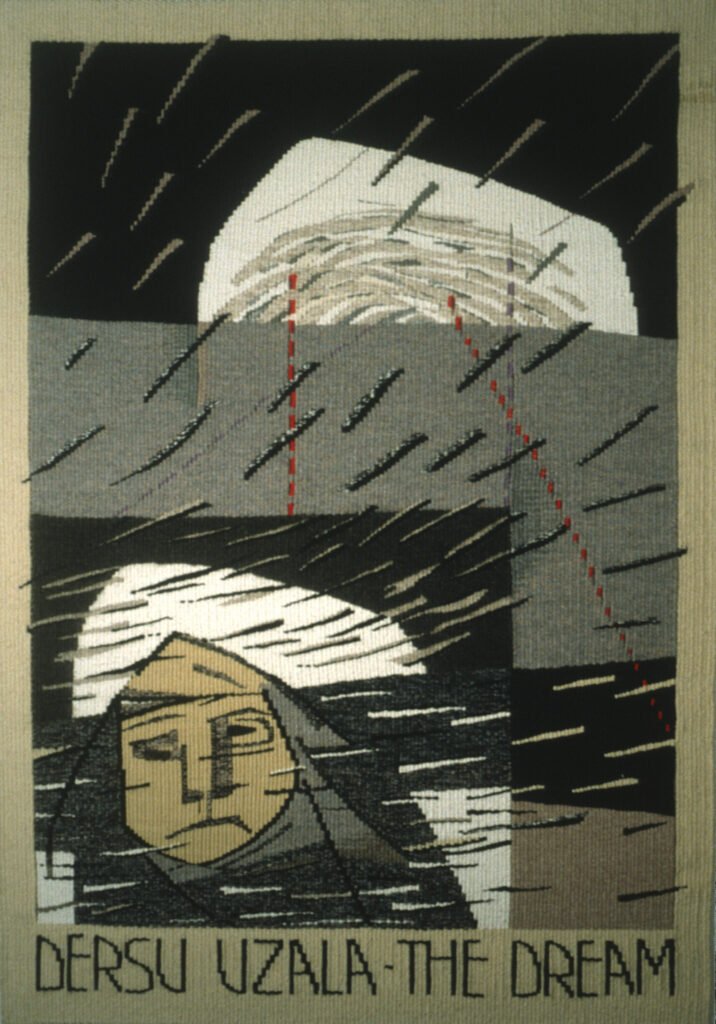

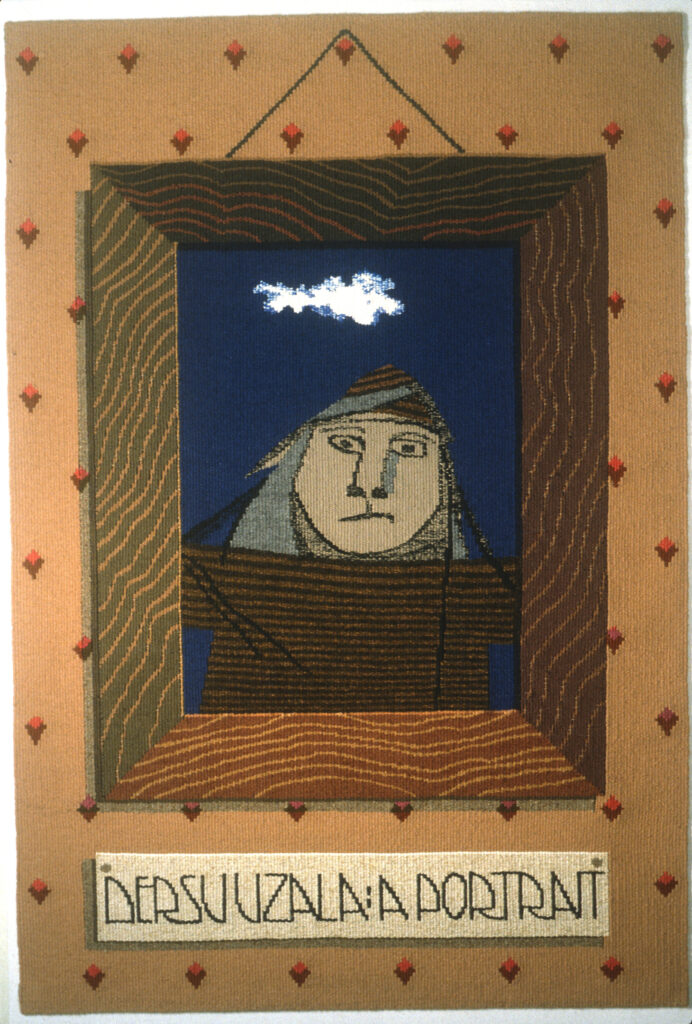

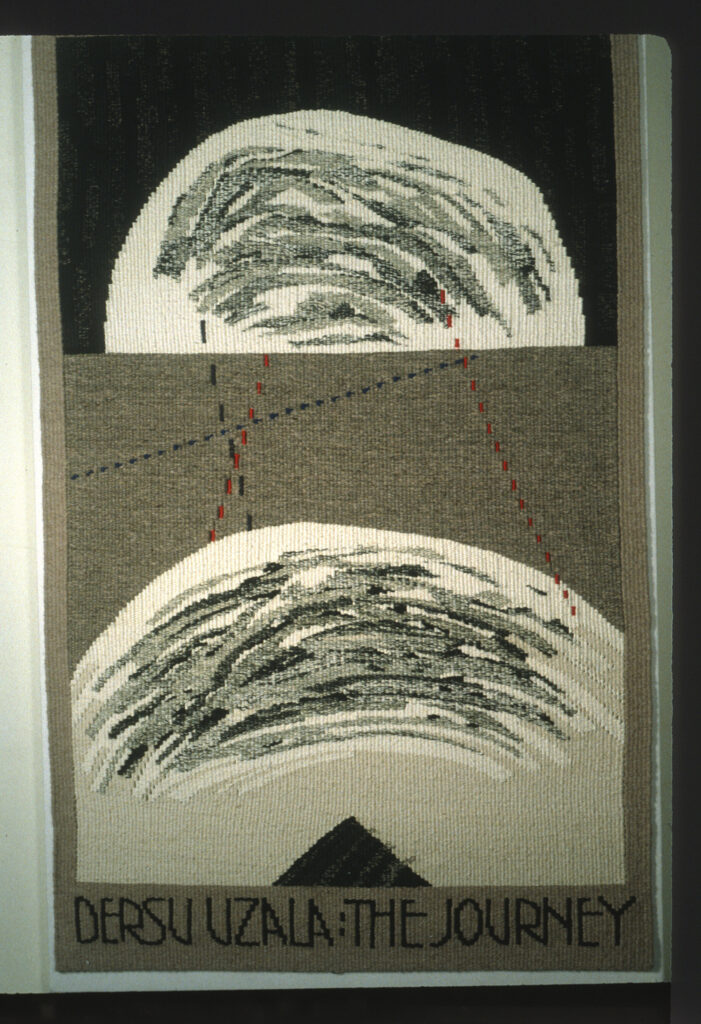

(left) A Portrait, 36″ x 24″ (center) The Journey, 36″ x 21.5″ (right) The Dream, 35.5″ x 24″

Dersu Uzala

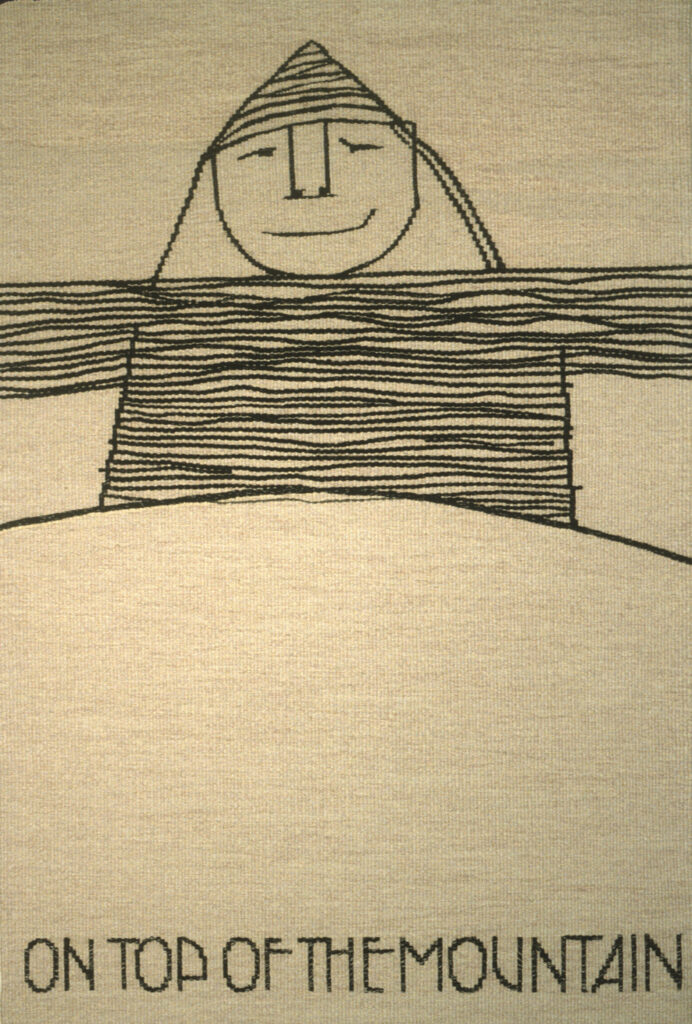

(left) The Way Beyond the Forest, 36.5″ x 24″ (center) The Ravens – An Omen, 36″ x 24,” (right) On Top of the Mountain, 36″ x 24.5″

Dersu Uzala

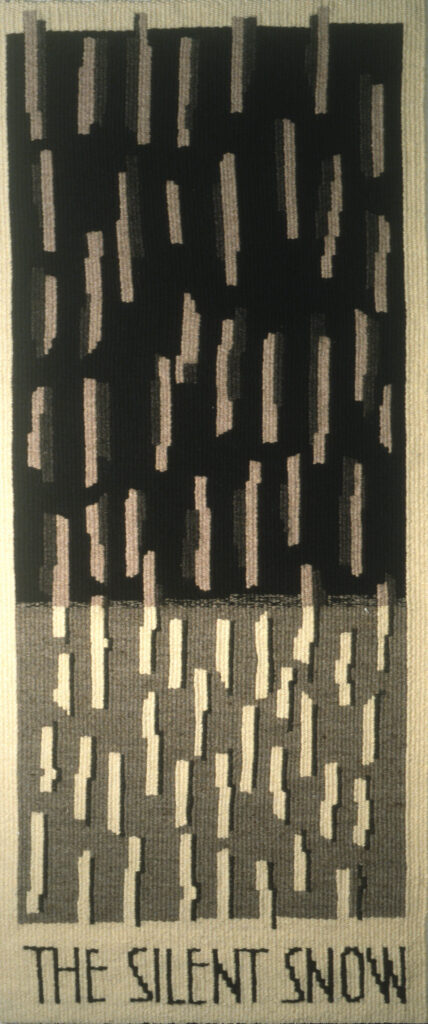

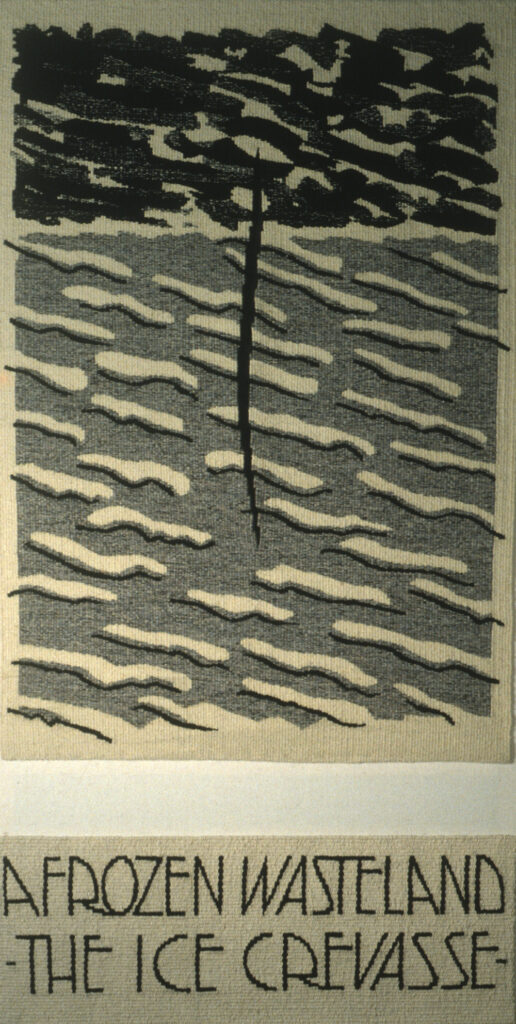

(left) The Silent Snow, 37.5 x 15.5″ (center) Through the Dark Trees, 36″ x 21.5″ (right) The Ice Crevasse, 36″ x 16.5″

Dersu Uzala

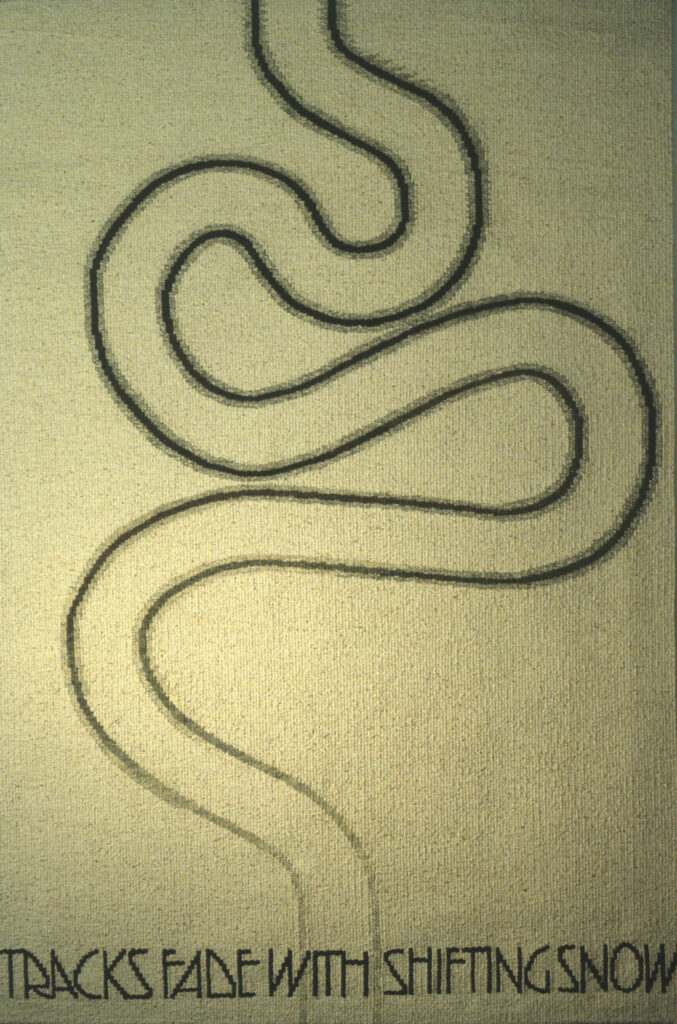

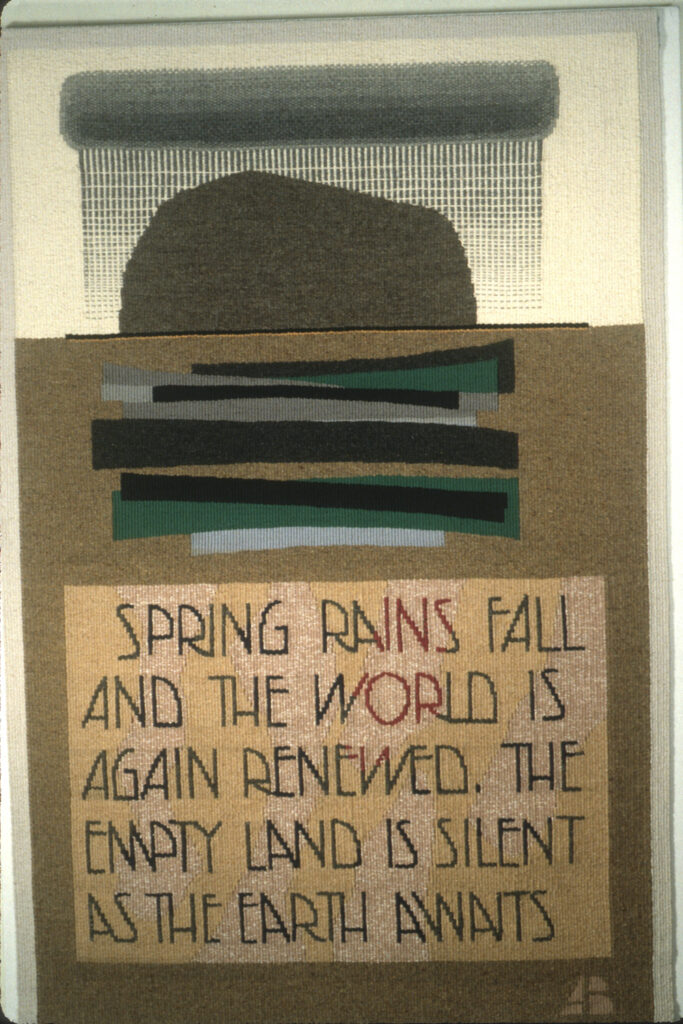

(left) A 2nd Storm, 36″ x 19″ (center) The Tracks Fade, 36″ x 24″ (right) The Earth Awaits, 36″ x 24″

Dersu Uzala, Akira Kurosawa’s 1980 movie, traces the wanderings of two Russian men whose very different life circumstances bring them together. Dersu, a nomadic hunter living in a northern boreal forest, pursues a winding path dependent upon the seasons and the movement of food resources. Capitan, the chief of a team of surveyors, follows a path determined by the geometry of land ownership. Despite of, or because of, these widely divergent impulses the two men’s journeys intersect. Dersu’s sensitivity to his environment becomes crucial to the survival of the surveyors and the companionship of the surveyors, especially Capitan, becomes pivotal to Dersu. The two men form a close friendship. In Kurosawa’s movie the lives of Dersu and Capitan epitomize the Western dichotomy of nature and culture. The intersection of the two men’s journeys highlights the characteristics that are associated with those realms, characteristics which are often considered to be in opposition.

For artists and writers journeys offer a rich mine of allegorical possibilities. For Archie Brennan the fortuitous experiences that arise from the curious mixture of direction and wandering that mark our lives brought him back to the movie, Dersu Uzala. It was Brennan’s own wandering path intersecting with a drawing by Sowdlu Nakashuk and the inadvertent alteration of that drawing by a cantankerous copy machine that spawned two series of tapestries, the first entitled “Dersu Uzala: An Allegorical Journey” and the second, “Dersu Uzala: The Earth Awaits”. Brennan was working at the time as an advisor to the Pangirtung tapestry workshop on Baffin Island in Canada.1 While exploring the possibilities of copying as a design aid for the Inuit weavers Nakashuk’s drawing of a village man was altered. The image that resulted reminded Brennan of Dersu. This image, as well as a series of drawings of the harsh Baffin Island landscape form the foundation for the two series. It is the second series which will direct my journey in this paper.

“Dersu Uzala: The Earth Awaits” consists of twelve tapestries, one which Brennan considers the beginning and one which he feels represents the end. The other ten pieces do not have a specific order. The artist has suggested that exhibiting them in a circle might be the most appropriate manner in which to view the sequence. Circularity is implicit in many world views, including the Inuit of northern Canada, with whom Brennan was working at the beginning of his creative journey with Dersu. This kind of thinking highlights the reoccurrence of events, such as seasonal change and biological rhythms. It contrasts with Western linear thinking which places events in a sequence with a beginning and an end. From a circular perspective the kind of events depicted in the middle ten tapestries, for example, “The Dream,” “The Silent Snow” and “Through the Dark Trees,” could have occurred many times in the course of Dersu’s life. They offer visual images of psychological moments in the protagonist’s journey, moments that might characterize any life journey – experiences of loss, of success, of portent, of insight and of danger. These incidents coalesce into a narrative, a series of evocative events in the life of Dersu Uzala. Even Brennan’s final tapestry, “The Earth Awaits,” as we shall see, serves as a catalyst for a new cycle. However, the entry point into the series is fixed and, in terms of the dichotomy of nature and culture, it is through an artifact of culture, the individual portrait.

Portraits are formal introductions. Rarely candid, they offer posed, intentional representations. In Brennan’s tapestry, “The Portrait,” we have not only a portrait of Dersu, but a picture of his portrait, a picture of a picture, twice removed, twice filtered from the reality that is Dersu Uzala, and he the product of a film maker. The layers of mediation are deep. The formal and constructed nature of the image stand in stark contrast to the Dersu we come to know in the film, an honest and animated man who relates in a very direct way to the natural and physical world around him. In the film Dersu’s existence depends on the change of seasons, the movement of animals, the subtle cues that those of us who live within the realm of urban culture rarely notice. Dersu’s wandering path is not concerned with straight lines, but with the organic. The Capitan, however, is an agent of culture. As an explorer and surveyor he precedes development, acting according to the desires of the state as he draws right angles across meandering rivers and rising mountains. His journey supports notions of cultural progress.

Who, we must ask, produced this portrait of Dersu? Could it have been made while Dersu lived with Capitan and his family in the city? Could this be a portrait hanging on Capitan’s drawing room wall, a memento of a close friend and a lifestyle so different from this formal setting? It is certainly not likely to have been commissioned by Dersu.

Dersu’s fixed countenance in the portrait suggests that he is bracing himself against some force about to throw his body off kilter. The undulating lines of the wood grain on the frame highlight the agitation of Dersu’s balancing act. As if the forces of nature were not challenge enough, Dersu is now subject to maintaining a fixed position within a rectangular wooden frame, a frame that imposes the same right angles of culture that his friend Capitan is mapping across the land. Lines which will change forever his nomadic, subsistence lifestyle. A small cloud hovers over Dersu’s head. Is this the friendly cloud of a summer day or an omen of an impending storm?

One of the remarkable qualities that unites Brennan’s work is the relationship that the image has to the surface of the tapestry and the conventions of representing three dimensions in two. In this piece the patterning of the wallpaper on which the portrait hangs can be read alternately as a flat two tone pattern or as a flocked (three dimensional) surface in which the darker color at the base of the red diamond is a shadow. The portrait itself hangs on top of this wall, its depth suggested by a shadow. The style of the portrait is almost completely flat; it is only the shadow of Dersu’s nose that raises the figure off the solid ground of blue sky. The juxtaposition within the Dersu series of flat shape dominated weavings with tapestries that refer strongly to an original line drawing or scumbled pencil work reflects the stylistic diversity that marks Brennan’s work as a whole. This melange of stylistic conventions highlights the tension that exists within a medium such as a tapestry, in which the image is usually rendered initially in a different medium, such as drawing or painting. Tapestry’s practitioners have argued endlessly about the relationship between the maquette and the tapestry. Many tapestry artists are seduced by tapestry’s imitative powers. Perhaps Brennan’s employment of multiple styles is commentary on this conundrum.

The sitter’s identity in “The Portrait” is revealed by the woven label, DERSU UZALA: A PORTRAIT. Words have figured prominently in Brennan’s tapestries, often becoming the content of the image itself. In the case of Dersu’s portrait the label adds an additional layer to the representation by imposing the artist’s identity onto the image. For surely, if this were a portrait of Dersu on Capitan’s wall, no label would be necessary. The label has been added by the artist, as it has to all the pieces in the series. It reminds us that this, like all images, is a re-presentation of a particular time and place, a re-presentation that is mediated through the eyes and hands of the artist. The layers of representation and illusion built into this image reflect the way experience is mediated through culture. The image is a simulacrum.2

The images in the ten middle tapestries, although not taken literally from the movie, are the kinds of events that could have taken place at any time in Dersu’s life – storms, snow falling, journeys across the land – all experiences of nature. Nonspecific in nature each one bears a psychological weight – the absolute stillness and calm of a winter day, the power inherent in land forms, the drama of a storm, the danger of unexpected hazards, the fear of losing one’s way. Because of their suggestive nature Dersu’s life becomes an allegory for the triumphs, the failures, the ambiguity and the questioning that mark human existence.

In “The Journey” broken red lines join two rounded mountains. The image is divided horizontally by a shift in the background value, suggesting geographical discontinuity. One of the mountains may be the journey’s origin and the other its destination. Yet the two hills appear so similar. No conventions of spatial recession help us navigate through the landscape. Perhaps the similarity of the journey’s origin and destination suggests that the process of getting from one point to another is more significant than the beginning and the end point.

Brennan has long spoken of tapestry weaving as a journey.3 He considers the fact that tapestries are created by building from one edge to the other to be of fundamental significance. Structurally, each pass builds upon those that precede it. For Brennan this structural attribute invites the weaver to approach the development of the image in the same way, allowing what has come before to determine, in part at least, that which follows. This approach raises another essential, and rhetorical, question. Should the fundamental qualities (be they seen as limitations or assets) of a medium affect the imagery used in that medium? Are all images appropriate for tapestry?

Brennan’s images often reflect the reality that tapestries grow from one edge to the other and for this reason one might assume that in “The Journey” the path begins at the bottom, where the weaving started. The tent or directional marker also guides our eye from bottom to top. Brennan has described his experience of weaving this series as an open ended journey of exploration which built upon itself as he revisited the narrative over a period of four years. For example, additional pieces were added to the series because they seemed to make sense in terms of what had already been woven. Thus not only within a piece, but also within the development of the series as a whole, the idea of process was critical.

Another feature of tapestry weaving considered to be inherent to the medium is that the image and the tapestry are one. The image is not applied on top of an already existing surface, it is created in the the weaving of the fabric. One result of this is that an image’s negative space is not the absence of the image making process as it often is for works on paper or canvas. The creation of the positive and negative space involves exactly the same process. This reality results, for some tapestry artists, in pieces that exhibit the horror vaccui of Medieval tapestries. For Brennan, however, the heightened awareness of the relationship between positive and negative space is influenced by Japanese prints and the contemporary form of unitized narratives, the comic strip. Brennan has always admired Reg Smythe the creator of Andy Capp and, indeed Dersu’s physical stature is reminiscent of Andy, a man whose life journey offered a different kind of force with which to contend. Both Ukiyo-e and comics employ a very conscious and economical use of line and space. The graphic simplicity and the interplay of positive and negative space that characterizes “The Ravens – An Omen” and “Through the Dark Trees” are examples of the degree of sophistication that marks Brennan’s compositional skills.

“Dersu Uzala: The Earth Awaits” ends with “The Earth Awaits.” It is in this piece that Brennan’s narrative departs from that of Kurosawa’s. In the film, Dersu moves to the city to live with Capitan and his family due to his failing eyesight. After a period of time Dersu leaves the city, presumably to return to the forest to die. Kurosawa leaves us with the implication of an end. However, Brennan’s series ends on a positive note. In “The Earth Awaits,” the land is replenished by the arrival of spring. If we consider the series in the circular format that Brennan has suggested, this tapestry cycles back to create a new beginning. Indeed the text of the piece, “Spring rains fall and the world is again renewed. The empty land is silent as the earth awaits” suggests this interpretation.

Optimism is also reflected in the use of brighter colors, which are absent in every other piece in the series other than “The Portrait.” If we follow the logic developed in the discussion of “The Portrait” earlier in the paper the color in the first tapestry is not necessarily the work of the artist. For Brennan has positioned himself in this image as an artist who is reproducing a portrait presumably created by another artist, and thus the color is not Brennan’s work; he is merely recording the portrait that someone else painted. Since “The Earth Awaits” is the final piece in the series we are only able to reflect in this way upon the artist’s use of color when we arrive at the end. It is then that we realize that the only image that Brennan created with color is “The Earth Awaits.” Of course we know that Brennan did create both the portrait and the image of the portrait, however, it is the ambiguity the artist has created with regard to his relationship to the image and the layers of mediation that that ambiguity creates that makes “The Portrait” so conceptually rich. This final puzzle of color that the artist offers us forces us to reflect back upon the entire series, thereby unifying the images and reinforcing the notion of circularity. It is this kind of intellectual and visual engagement that rewards the viewer of “Dersu Uzala: The Earth Awaits.”