This article was first published in Fiberarts Magazine, Summer 2010.

In the midst of a tapestry postcard exchange in 2003, Dorothy Clews, who lives in St. George, Australia and Linda Wallace, who resides in Nanoose Bay, British Columbia asked each other a simple question: “How should one dispose of an unwanted tapestry?” Dorothy, an avid gardener, suggested composting. Her response spawned an ongoing project in which both artists have woven tapestries for the sole purpose of planting, exhuming, and then considering the expressive potential of the partially decayed textiles. The experiment has been fueled by a scientific curiosity, a willingness to cede control to the power and vagaries of nature, and an openness to serendipity.

For Wallace, this body of work engages an ongoing subject of her artwork: infertility. The buried tapestries comprised of wool and linen contain woven images of seeds. Wallace refers to “implanting” the tapestries into the soil and she measures the time they spend in the ground in “trimesters.” The inability of these planted seeds to germinate is symbolic of the failure of some women to conceive. Each subsequent tapestry that Wallace wove for this project contained fewer seeds, “echoing the diminishing possibility of fertility as a woman ages.” (Wallace, Artist Statement, February, 2010)

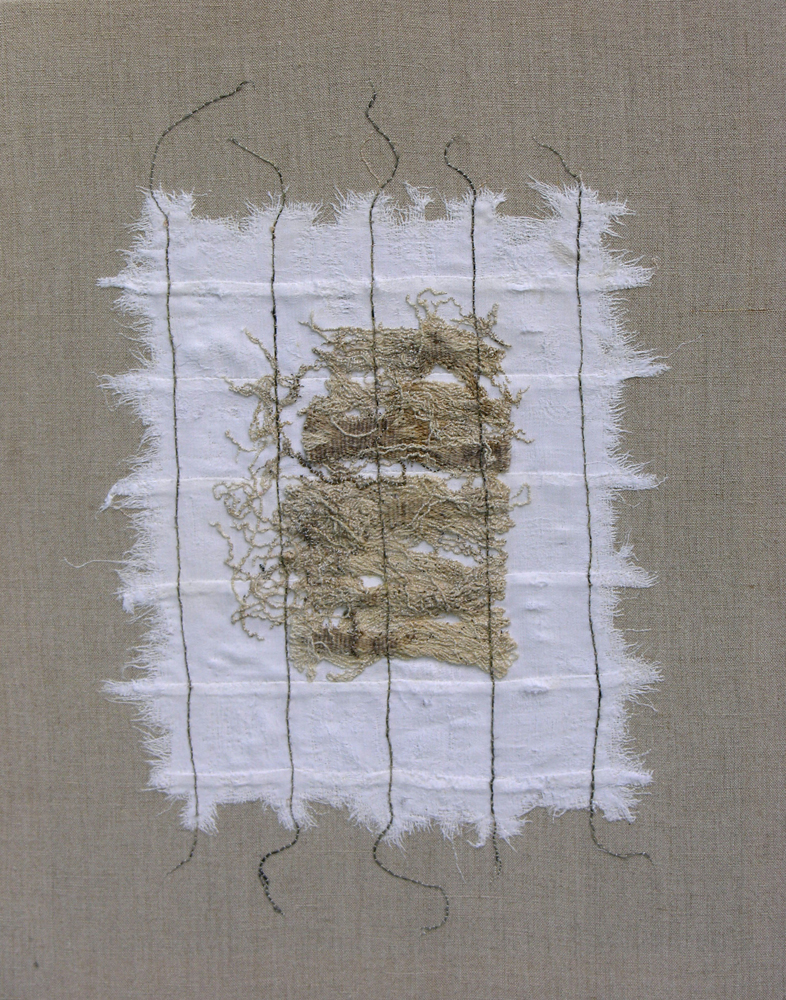

Implantation Series: Diminishment of Hope: NonGravid, 22 July belongs to a group of tapestries that Wallace buried on the winter solstice. The first tapestry was exhumed three months later, at one trimester. Subsequent removals occurred at one-month intervals. During the time the tapestries were buried, Wallace tended her plantings by monitoring the soil temperature, hours of sunshine and rainfall. Her photographs documented the growth of plants that colonized the disturbed soil. Before the tapestries were unearthed, Wallace consulted textile conservators to learn about stabilizing the decomposing tapestries. After the weavings were superficially cleaned and dried, they were carefully washed and thoroughly rinsed.

During the time that Wallace was working on this project, she lost both her mother and father. As she sorted through their belongings, she decided to mount the fragile tapestries on family linens. She tore the linens into strips in order to suggest the cloth used to swaddle infants and to prepare the deceased for burial. The strips were sewn together and the tangled warp and weft threads of the tapestry were carefully couched to the pieced linen. Wallace then abraded the heritage linens with rocks and sand paper.

The repetitive nature of couching and the resulting accumulation of a mass of small stitches, echoes Wallace’s drawing style, in which layers of fine pencil strokes coalesce to form an image. It is also similar to the process of tapestry itself, in which the image unfolds as passes of weft build upon each other, one at a time. Wallace’s attitude towards all of the artistic processes she employs is that of a collaborator. Instead of starting with a finished image in her mind, she allows each drawn, woven, or stitched mark to influence the direction and final form of the piece. “There’s a magic in watching the imagery emerge from line after line laid down in a dance between serendipity and intention.” (Wallace, Artist Statement, February 2010) Her willingness to engage the technical process as a partner is also evident in Wallace’s acceptance of decomposition as an active agent in her work.

Wallace’s work is an open-ended journey that celebrates handwork normally associated with women: weaving, planting and sewing. By using these traditionally female pursuits in the service of work that is rich with intellectual, emotional and aesthetic content, she challenges stereotypes associated with the domestic. The melancholy that might be associated with Wallace’s chosen subject, infertility, is balanced by the hope and rebirth implicit in the conservation and reclamation of the decomposed tapestries. The subtle and fragile beauty and the meticulous craftsmanship in Wallace’s work speak to the strength and resiliency of life itself.

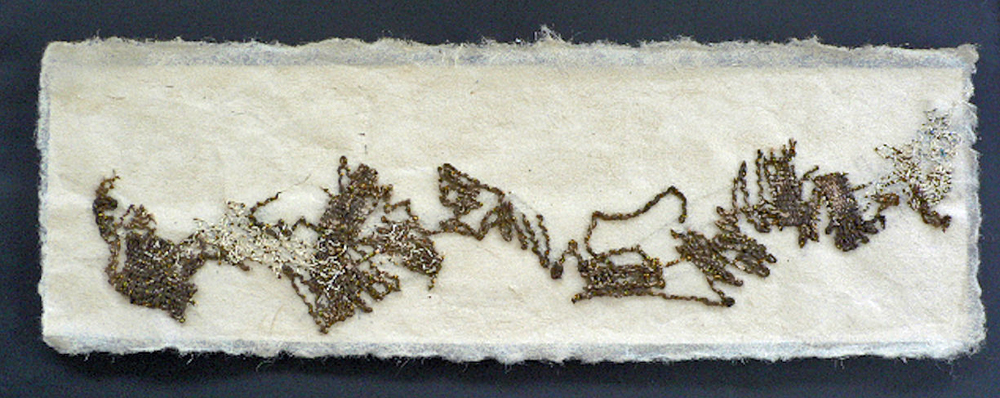

Dorothy Clews, Pulse, Panel, 17cm x 53cm

Dorothy Clews’ work with buried tapestries reflects her interest in gardening and her environmental concerns. “The landscape is the subject of the tapestry, but the natural environment has an influence on the form that the tapestry will take.” (Clews, Artist Statement, September 2008) When she buries her tapestries they become a part of the landscape and through decay, a part of them remains as landscape.

Clews’ home is subject to cycles of drought and flooding. She buried her tapestries over the period of a year so that they would become a climatic record. During the dry period, change in the tapestries was negligible. When rain finally flooded her planting ground, the fabric broke down quickly. Ironically, the same rain that brought new life and growth to the desert surrounding her home also initiated the decomposition of her tapestries. And, in turn, it was the disintegration of the cloth that provided the creative stimulus for the artist’s subsequent work with the fragmented tapestries.

Clews calls this body of work, “Field Trials.” Each tapestry mimics the long rectangular plot in which a farmer tests seed varieties. By burying her work, Clews tested the susceptibility of different weft materials to decomposition. Loosely spun weft fibers tended to protect the warp yarns from decay. Silk rags remained intact, while raw silk dissolved.

After Pulse was disinterred and carefully cleaned Clews discovered that, “ The seine twine warp had disappeared, the hemp weft had become brittle and slightly felted, small feathery rootlets intertwined in the yarn. The tapestry had become a record of the sun, heat, rainfall and growth of plants.” (Clews, The Significance of Absence, Canadian Tapestry Network Newsletter Winter 07-08)

Clews found that the selvedges and the edges of shapes within the tapestry degraded more significantly than the interiors of the forms. She compares the accelerated change at the tapestry’s edges to the liminal zones between ecosystems, zones known for their greater biological productivity and potential for evolutionary transformation. It was the frayed edges of the textile that would become the focus during the conservation of the buried tapestry and that would provide the most potential for artistic intervention.

The fragile and tattered remains of Pulse reminded the artist of the appearance of tracts of land in her region that lay depleted after years of monoculture. Agricultural land is considered to be productive and useful, and is contrasted with the surrounding desert, which is seen as wild and barren. For Clews, this categorization is simplistic, focusing only on the land’s ability to provide sustenance for humans. “Between artifact and earth, between culture and nature, is an intersection of other realities where wildness becomes comprehensible.”(Clews, Artist Statement, January 2010)

As an artist, Clews is part of culture; she creates forms by manipulating materials, by weaving fibers into cloth. Yet she also welcomes nature as a partner in her work, subjecting the woven cloth to the transformative forces of water and microbial action. The relative power of nature and culture flips again as the artist takes the decayed cloth and, through conservation and mounting, asserts the creative force of culture. In the metaphor of landscape and nature, Clews work is an experiment that brings together fabric and soil in a sort of cross pollination out of which new forms sprout.

Wallace’s and Clews’ work embodies, both literally and figuratively, the cycle of creation and destruction and the hope of rebirth through conservation. For both artists this project has led to an increased sensitivity to an essence that is embedded within the textile itself, an essence that persists through the changes that the tapestries undergo. It is this fundamental quality of the woven cloth that both artists respect and honor as they explore the transformative power of nature.